The manifestation of the Vedas in human society

The Vedas don’t have a material origin; they are a divine transcendental vibration that is transmitted to Brahmā and in this way become known within this particular universe.

« Vedānta-sūtra: The Govinda-bhāṣya of Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa

Sūtra 1.3.29 - The manifestation of the Vedas in human society

ata eva ca nityatvam

ataḥ: therefore, for this reason; eva: same; ca: and; nityatvam: eternity.

Therefore, the eternity of the Vedas is proved.

Commentary: At the beginning of each of his days, Brahmā again creates the universe by remembering and reciting the words from the Vedas. Therefore, although the creation of Brahmā is temporary, the words of the Vedas are eternal. The Vedas don’t have a material origin; they are a divine transcendental vibration that is transmitted to Brahmā and, in this way, becomes known within this particular universe.

However, one could question how the Vedas can be eternal if the different books that compose the Vedas were spoken by different sages at different times. How can something that has a beginning be called eternal?

The answer is that these sages are merely speakers and not the real authors of the Vedas. Even Vyāsadeva himself just compiles knowledge that is previously available.

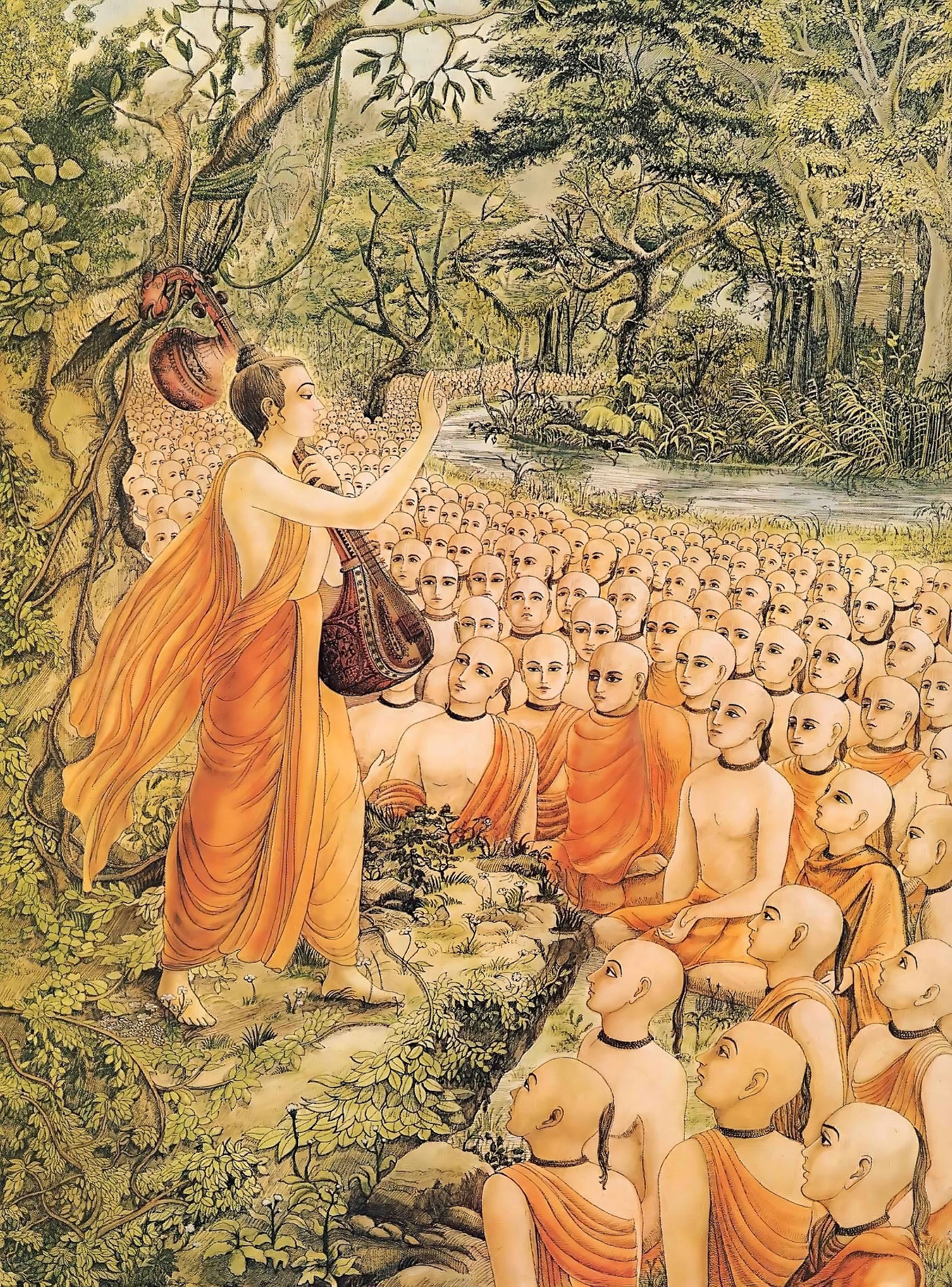

All the Vedas come originally from Kṛṣṇa and become manifested in the mind of Brahmā, who uses their knowledge to create the universe. This knowledge is then transmitted to his mental sons (like Nārada, the Kumāras, and others), who in turn transmit it to different sages, kings, and other personalities across the universe.

Although different parts of Vedic knowledge can become lost on our planet at different times (it’s estimated that currently, only 7% of the original verses compiled by Vyāsadeva are still available, for example), the knowledge continues to exist in higher planetary systems, and it can be again transmitted to humanity by great sages who have it. When this happens, the sage in question becomes known as the speaker of a certain book, although the knowledge in itself is eternal. If the disciplic succession of a certain book is broken and the knowledge is lost, Kṛṣṇa may personally come to restore it, as He mentions in the Bhagavad-gītā (4.2): “This supreme science was thus received through the chain of disciplic succession, and the saintly kings understood it in that way. But in course of time the succession was broken, and therefore the science as it is appears to be lost. That very ancient science of the relationship with the Supreme is today told by Me to you because you are My devotee as well as My friend and can therefore understand the transcendental mystery of this science.”

Sūtra 1.3.30 - How the Vedas survive the universal cycles of creation and destruction

samāna-nāma-rūpatvāc cāvṛttāv apy avirodho darśanāt smṛteś ca

samāna-nāma-rūpatvāc: on account of the similarity of name and form; ca: also; avṛttāu: in the repetition (of cycles of creation); api: also, even; avirodhaḥ: absence of contradiction; darśanāt: because of the śruti; smṛteś: because of the smṛti; ca: indeed.

Indeed, because the names and forms remain the same in each new cycle of creation, there is no contradiction. This is confirmed in the śruti and smṛti.

Commentary: The Vedas describe different cycles of creation and destruction. The first is the sequence of four eras (Satya-yuga, Treta-yuga, Dvāpara-yuga, and Kali-yuga) that affect our planet. The earth is populated at the beginning of Satya-yuga, and with the passage of the eras, humanity gradually degrades, with qualities such as knowledge, austerity, mercy, and so on declining by one-quarter at the passage of each yuga. Similarly, life expectancy is reduced by 90% with the passage of each era, and the general strength and health also decline. Humanity goes thus from a community of pure sages who live for 100,000 years in the beginning of Satya-yuga to tribes of cannibal barbarians who live for not much more than 20 years at the end of Kali-yuga. When the degradation reaches an extreme, Kalki comes to annihilate these degraded atheists and start a new cycle.

The next cycle is the Manvantara, which affects the higher planetary systems. A Manvantara is composed of 71 sets of the four yugas and lasts for a total of 306,720,000 years. All the Devas, led by Manu, stay in their posts for the period of a single Manvantara. When the period is concluded, they are promoted to Maharloka and a new Manu, as well as a new generation of demigods, take their places. The demigods thus just assume and release their posts following this schedule, just like politicians being appointed and demoted from certain functions. In some cases, certain personalities may wait for several Manvantaras to assume a certain post. Daksa, for example, was reborn close to the end of the first Manvantara after his offenses to Lord Śiva, but regained his post only at the beginning of the 6th Manvantara.

At the end of each day of Brahmā, the universe is partially destroyed, with the lower, intermediate, and celestial planetary systems (up to Svargaloka) being burned by the fire created by Lord Ananta. However, Brahmā recreates everything at the beginning of his next day using the transcendental sound vibration of the Vedas.

However, what happens after pralaya, the complete destruction at the end of the life of Brahma? One could question how the Vedas can be eternal if everything is destroyed, including the universe itself and the disciplic succession that transmits the Vedas. How can the Vedas be eternal in this context of complete destruction?

To this, Vyāsadeva replies: samāna-nāma-rūpatvāc cāvṛttāv apy avirodho darśanāt smṛteś ca. The Vedas are not lost. They are again transmitted to the next Brahmā in the following cycle of creation. The demigods and other beings are then recreated with the same forms as before, and thus there is no contradiction. He adds that this is also proved by both the śruti and the smṛti. In other words, the Upaniṣads, as well as the Purāṇas, the Mahabharata, and other scriptures agree on this point.

Śrīla Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa quotes several passages in his commentary to support this point, including sources from both the śruti and smṛti:

ātmā vā idam eka evāgra āsīt sa aikṣata lokān utsṛjāḥ

“Indeed, at the beginning there was only the Supreme Personality of Godhead. He thought: ‘I shall create many worlds.’” (Aitareya Upaniṣad 1.1)

yo brahmāṇam vidadhāti pūrvam

yo vai vedāmś ca prahiṇoti tasmai

tam ha devam ātmabuddhi-prakāśam

mumukṣur vai śaraṇam aham prapadye“He who, in the beginning, instructed Brahmā, He who indeed also delivered the Vedas. Unto that divine Person, the revealer of the knowledge of the Self and giver of liberation, I completely surrender.” (Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad 6.18)

sūryā-candramasau dhātā yathā-pūrvam akalpat

“Brahmā created the sun and moon as he had done before.” (Rg Veda)

nyagrodhaḥ su-mahān alpe, yathā bīje vyavasthitaḥ

samyame viśvam akhilam, bīja-bhūte yathā tvayi“O Lord, just as a great banyan tree rests within a tiny seed, in the same way at the time of cosmic devastation the entire universe rests within You, and remains under Your full control.” (Viṣṇu Purāṇa)

nārāyaṇaḥ paro devas

tasmāj jātaś caturmukhaḥ“Nārāyaṇa is the Supreme Personality of Godhead. From Him, the four-faced Brahmā was born.” (Varāha Purāṇa)

tene brahma hṛdā ya ādi-kavaye

“It is He only who first imparted the Vedic knowledge unto the heart of Brahmājī, the original living being.” (Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam 1.1.1)

Brahmā lives for an extremely long period of time, corresponding to a period of 311.04 trillion years. However, like everyone else, his life eventually comes to an end. The death of Brahmā coincides with the final destruction of the universe and the inhalation of Mahā-Viṣnu. At this point, all the material universes are completely destroyed, and all conditioned souls are put to sleep inside the body of Mahā-Viṣnu. This period lasts for the same 311.04 trillion years as the life of Brahmā.

At the end of this period, Mahā-Viṣnu desires to again create the material universes as they were before, giving names and forms to all the conditioned souls, so they can be engaged in another cycle of material existence and have another chance of going back home, back to Godhead. He thus initiates the process of creation by exhaling all the universes and entering each of them as Garbhodakaśāyī Viṣnu and Kṣīrodakaśāyī Viṣnu. This leads to the appearance of new Brahmās in each universe, and so on.

The Lord then manifests the Vedas exactly as they were before and transmits them to each Brahmā from inside the heart. Possessing all the Vedic knowledge, the Brahmās can then engage in the process of performing the secondary creation, giving forms to all living beings and thus offering them a chance to practice self-realization and regain their eternal spiritual forms. All the demigods (as well as other creatures) are created again, exactly as before, from the archetypal forms described in the Vedas. Different souls, who possess the required qualifications, enter into these bodies and, impelled by the three modes of nature, act as demigods, performing the required functions.

Sūtra 1.3.31 - An argument from Jaimini

madhv-ādiṣv asambhavād anadhikāram jaiminiḥ

madhu-ādiṣu: in madhu-vidyā and other Vedic meditations; asambhavāt: because of impossibility; anadhikāram: qualification; jaiminiḥ: Jaimini.

Jaimini is of the opinion that devas do not engage in the madhu-vidyā and other forms of Vedic meditation and duties because it is not possible for them to do so.

Commentary: In this sūtra, another question is raised: Many processes of meditation and worship described in the Vedas include meditation and worship of the demigods. The madhu-vidyā, for example, described in the Chāndogya Upaniṣad, describes the Sun as a great honeycomb that is enjoyed by the demigods. The sun rays, spreading throughout the universe, are the honeycombs, and the Vedic mantras are the bees that collect the nectar of the Vedic rituals, which are compared to flowers. This great honeycomb gives pleasure to the demigods and should be worshiped by all.

The purpose of this meditation is to see the Lord as the essence of the sun, the unifying principle behind the whole cosmos. The whole process of Vedic sacrifices and other auspicious activities has the goal of satisfying Him, and by this process of satisfying the Lord, all demigods and, in fact, all beings are satisfied. By this process of meditation, one can obtain everything desired, including a position on the celestial planets, up to the post of one of the principal devas or vasus, but the ultimate goal of this process is to satisfy the Supreme Lord.

It’s quite natural for human beings to practice this process of meditation, as well as other forms of worship prescribed in the Vedas, seeing the different demigods as parts of the universal arrangement created by the Lord and as exalted servitors of the Lord. It is also not unnatural for human beings to desire promotion to the celestial planets as a result of performing such duties. However, what about the demigods? Not only are they worshiped as part of the process, but they have already attained positions in the celestial planets.

Jaimini ṛṣi, the propounder of the provisional path of Karma-Mīmāmsā, is of the opinion that the madhu-vidyā and other similar processes of meditation are just for human beings, and can’t at all be practiced by demigods, because these systems of meditation include meditating on the forms of demigods, and thus it does not make sense for demigods to meditate in their own forms. According to this argument, one can’t simultaneously be the worshiper and the object of worship. Apart from that, the result of these processes of meditation is to become a vasu or a deva, and thus it does not make sense for those who are already occupying these positions.

Instead, he argues, the demigods must meditate only in the light of the impersonal Brahmajyoti, as described in the next sūtra, jyotiṣi bhāvāc ca, rejecting any other type of meditation. These ideas, however, are contested by Vyāsadeva, who gives his conclusion in sūtra 1.3.33.

Sūtra 1.3.32 - Another misconception

jyotiṣi bhāvāc ca

jyotiṣi: in the Supreme light; bhāvāt: because of existence; ca: and.

The demigods can’t perform these types of worship because they meditate on the effulgence of the Lord, the supreme light, he argues.

Commentary: This is another argument by Jaimini, who argues that another reason for the demigods not being capable of performing the madhu-vidyā and other types of Vedic meditation and duties is that they worship the impersonal Brahmajyoti, the effulgence of the Supreme Lord. Because they already have this fixed position (bhāvāt), he argues that they have no need of engaging in other types of worship.

This can be supported by a passage of the Bṛhad-āraṇyaka Upaniṣad (4.4.16):

tad devā jyotiṣām jyotir āyur hopāsate ’mṛtam

“The demigods worship the Supreme Lord, the light of lights, the cause of all beings, the immortal existing beyond time.”

Now, Vyāsadeva gives his conclusion.

Sūtra 1.3.33 - Vyāsadeva gives the conclusion

bhāvam tu bādarāyaṇo’sti hi

bhāvam: existence; tu: but, however; bādarāyaṇaḥ: Vyāsadeva; asti: is; hi: because.

Vyāsadeva, however, maintains that the demigods perform the Vedic duties, but with a specific mentality.

Answering the arguments of Jaimini, Vyāsadeva uses the word “tu” (but, however) to clear the doubt. Jaimini has his opinion, but the conclusion of the compiler of the Vedas is different.

The devas do perform different types of duties and meditations recommended in the Vedas, including the madhu-vidya and other systems of meditation that involve meditation on demigods. This may at first appear to not make much sense. Why do the demigods meditate on themselves? The reason is indicated by the word “hi”. When the demigods meditate on the devas and ādityas, they are not meditating on themselves, but indirectly meditating on the Supreme Personality of Godhead, as the archetypal deity, the Supreme amongst all controllers.

Everything that exists is connected with the Lord. In the Second Canto of the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, for example, we are taught how to meditate on the universal form, seeing different parts of the creation, such as the rivers, mountains, planetary systems, and powerful personalities as parts of His cosmic body. Because this meditation connects these manifestations with Him, it ultimately helps one to become Kṛṣṇa conscious. Similarly, when demigods meditate on devas and ādityas as being manifestations of the Supreme Lord (instead of just meditating on themselves), they gradually advance in their Kṛṣṇa Consciousness.

The process is that the demigods perform the madhu-vidya and other types of meditation and, in this way, attain the result of these meditations, which is to become devas again in the next kalpa. In this next birth, they again perform these types of meditation, meditating on the Lord as being the original person and the source of all demigods. As a result of this meditation, they eventually become liberated.

The names of different demigods, such as “Indra”, “Surya”, and so on, are originally names of the Lord. In the Vaikuṇṭhas, there are different expansions of Lord Viṣnu who bear these names, and the demigods in the material universes simply borrow these names (as well as their powers) from them. When the demigods meditate on the devas, they are actually meditating on these different expansions of the Lord, who are the source of their powers.

Another point made by Śrīla Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa is that demigods understand that they are temporary, and thus they desire to become demigods again in their next lives. Just because a man already has sons in this life, it does not mean that he will not desire to have sons again in his next life. Similarly, even having attained the exalted position of demigods, the devas are concerned about their next lives and desire to attain the same positions again, to continue their worship of the Lord.

This is corroborated in many passages of the scriptures, where it is mentioned that the demigods perform sacrifices and meditation. The same verse 4.4.16 from the Bṛhad-āraṇyaka Upaniṣad that was used to support the view of Jaimini, also serves to confirm the correct conclusion: tad devā jyotiṣām jyotir āyur hopāsate ’mṛtam, “The demigods worship the Supreme Lord, the light of lights, the cause of all beings, the immortal existing beyond time.”

It’s also said that:

prajāpatir akāmayata prajāyeyeti sa etad

agnihotram mithunam apaśyat tad udite sūrye ‘juhot“Prajāpati (Brahmā), desired: ‘Let me create children.’ He then saw two agnihotra sacrifices. When the sun rose, he offered oblations into the fires.” (Taittirīya-brāhmaṇa 2.1.2.8)

devā vai satram āsata

“The devas then performed a Vedic sacrifice.”

Apart from performing sacrifices and meditation in order to again attain the posts of demigods in their next lives, the demigods perform these sacrifices by the order of the Supreme Lord, with the goal of protecting the universe.

One could argue that since the demigods want to ultimately attain liberation, why do they practice such an indirect process, which can take several kalpas to be concluded? The point is that each soul in the material world has free will to choose his path. Some come to understand the real nature of this material world and try to find a direct process to become free of it, while others are more attracted to indirect processes. The demigods are souls who attain a very high level of piety, but who are simultaneously attached to material enjoyment. Because of this, although they are very close to liberation, they still have to stay for a long time in this material world before finally attaining it. In the meantime, the Lord engages them in performing administrative tasks and maintaining this material world.

Another point brought up in these two sūtras is that if even the demigods perform sacrifice and meditation according to the recommendations of the scriptures, we human beings should be even more dedicated to performing our duties.

Exercise

Now it’s your turn. Can you answer the following arguments using the ideas from this section?

Opponent: “The claim that the devas are embodied jīvas, who possess material bodies, and are capable of performing vidyās such as the madhu-vidyā is absurd.

First of all, the śruti often speaks of a single deva acting in many places at once, such as being present in numerous sacrifices. A material body can’t be simultaneously present in numerous locations. Some great yogis can divide themselves into eight forms, but even then, they can perform only a single activity at once.

Second, if devas are born and die, then before the birth of a deva and after his death, Vedic names such as ‘Indra’, ‘Varuṇa’, etc., would be meaningless, and therefore the scriptures couldn’t be considered eternal. According to the Mīmāṃsā principle, the relation between name and the object named in the Veda is eternal; therefore, these names must denote eternal, non-material forms, and not perishable embodied individuals.

Third, in meditations like the madhu-vidyā, the object and the worshiper cannot be the same; a deva cannot both be the honey (object) and the meditator at the same time. Nor do devas desire the fruits of the meditation (to become vasus, ādityas, etc.), since they already are such. In this way, devas have no adhikāra (qualification) for those vidyās. Instead, the devas meditate on the supreme light, which is a different practice, with a different object.

To argue that at each creation Brahmā remembers Vedic words and prototypes to fashion bodies does not solve the problem of the relation between name and the object named after the destruction of the universe. If everything is destroyed, then we have to:

a) Accept that the Vedas have to be re-created at every cycle of creation (then how can we say they are eternal?)b) Or, if we accept that the Vedas continue to exist after dissolution, when the demigods mentioned cease to exist, then we have to accept that at this time the words of the Vedas become meaningless.

In either case, the argument is contradictory and thus flawed. Our explanation remains the only logical explanation. Therefore, to preserve the eternity of Vedic words and avoid contradictions, devas should be regarded as bodiless, timeless archetypes, and not embodied jīvas. They are not eligible for those meditations that have the deva forms themselves as the object.”

Description: The argument that the demigods have no physical bodies comes from the Pūrva-Mīmāṃsā philosophy. As previously mentioned, this is a provisional philosophy taught by Jaimini with the goal of putting ordinary men on the path of piety of the Vedas, convincing them to perform their duties in the varṇāśrama system and perform Vedic ceremonies with the goal of being elevated to heavenly planets.

To that end, Jaimini overemphasized the importance of the demigods and fruitive activity, while avoiding entering into details about the supremacy of the Lord. Because Mīmāṃsakas interpret verses of the scriptures starting from the wrong conclusions, they can’t penetrate into the intricacies of the scriptures. Jaimini himself, although well-intentioned, is not entirely correct in all of his conclusions, as indicated in this section.

You can also donate using Buy Me a Coffee, PayPal, Wise, Revolut, or bank transfers. There is a separate page with all the links. This helps me enormously to have time to write instead of doing other things to make a living. Thanks!

« Vedānta-sūtra: The Govinda-bhāṣya of Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa