4.3: Sankhyopasangrahādhikaraṇam - The five pañca-janās

Even if we were to consider the passage [from the Bṛhad-āraṇyaka Upaniṣad] as meaning five groups of five, it doesn’t match the Sānkhya theory, because the number exceeds the Sānkhya counting

« Vedānta-sūtra: The Govinda-bhāṣya of Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa

Topic 3: Sankhyopasangrahādhikaraṇam - The five pañca-janās

Pañca-pañca-janāḥ does not refer to the 25 elements of Sānkhya

na sankhyopasangrahād api nānā-bhāvād atirekāc ca, prāṇādayo vākya-śeṣāt, jyotiṣaikeṣām asaty anne

“Even if we were to consider the passage [from the Bṛhad-āraṇyaka Upaniṣad] as meaning five groups of five, it doesn’t match the Sānkhya theory, because the number exceeds the Sānkhya counting, and because the groups don’t correspond to the disposition of the elements in the living entities. The five units described in the passage are prāna and the rest, as mentioned in the subsequent verse in the passage.

In another recension of the text, the word jyotis is found, while the word anna is absent.”

Sūtra 1.4.11 - Counting the material elements

na sankhyopasangrahād api nānā-bhāvād atirekāc ca

na: not; sankhya-upasangrahāt: because of enumeration according to the Sānkhya system; api: even (if assumed); nānā-bhāvāt: because of diversity of nature (mismatch of subcategories); atirekāt: because of excess; ca: and.

Even if we were to consider the passage [from the Bṛhad-āraṇyaka Upaniṣad] as meaning five groups of five, it doesn’t match the Sānkhya theory, because the number exceeds the Sānkhya counting, and because the groups don’t correspond to the disposition of the elements in the living entities.

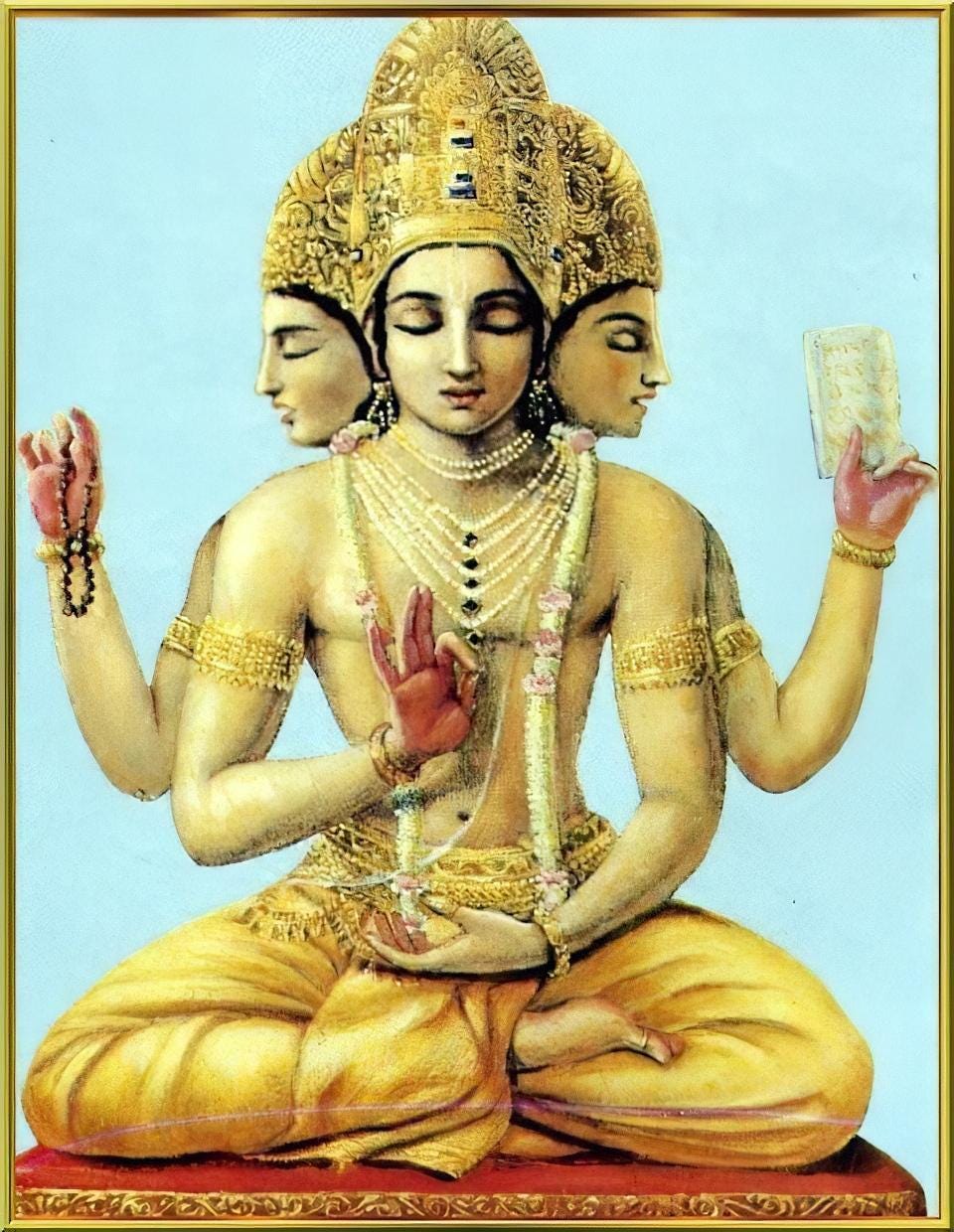

Commentary: The original Sānkhya philosophy, explained by Lord Kapila in the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, includes the counting of the material elements. The idea is that by understanding the material elements and the interactions between them, one can better understand how the material world works and thus find his way out. We identify strongly with the pains and pleasures of this world when we are under the impression that they are real. As soon as we can understand how the material illusion works, it becomes easier to free ourselves and observe it from afar.

In the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, Lord Kapila describes 24 material elements:

1- The five gross elements (earth, water, fire, air, and ether).

2- The five subtle elements (smell, taste, color, touch, and sound).

3- The four internal senses (mind, intelligence, ego, and contaminated consciousness).

4- the five senses for gathering knowledge (the auditory sense, the sense of taste, the tactile sense, the sense of sight, the sense of smell).

5- The five outward organs of action (the active organs for speaking, working, traveling, generating, and evacuating).

To these 24 elements, a 25th element can be added: the time factor, which acts as the mixing element, putting the material manifestation into action. This time element represents the influence of the Supreme Personality of Godhead, who is behind the entire material manifestation. In this way, the original theistic Sānkhya philosophy counts the material elements as a way to ultimately bring one to the Lord.

The atheistic Sānkhya also offers a counting of 25 material elements, but it is different from the original and excludes any reference to the Lord, considering prakṛti, the material nature, as the ultimate cause.

In this counting, the 25 elements are prakṛti (material nature), puruṣa (the soul), mahat-tattva (the great material principle), ahankāra (false ego), manas (the mind), ākāśa (ether), vāyu (air), agni (fire), apas (water), pṛthvī (earth), śravāmsi (sound), ākṛti (form), sparśa (touch), rasa (flavor), gandha (aroma), śrotram (hearing), tvak (touch), dṛk (sight), rasana (taste), nāsikāḥ (smell), rasanām (tongue), karau (hands), pādau (feet), prajananam (genital), apānaḥ (anus).

The atheistic Sānkhya philosophers naturally want to promote their view as correct, and thus they try to find support for it in the Vedic literature. However, the Vedic scriptures offer a fundamentally theistic view of the universe, and there is not much support for a theory that excludes the Lord from the material creation.

One of the few passages that appear to vaguely support it is Bṛhad-āraṇyaka Upaniṣad 4.4.17:

yasmin pañca-pañca-janā

ākāśāś ca pratiṣṭhitāḥ tam eva manya ātmānam

vidvān brahmāmṛto ‘mṛtam“He, in whom the pañca-pañca-jana and the ether element are established, you should know as the Supreme Self. The sages, knowing Him as the immortal Brahman, become also immortal.”

Pañca means “five”. The verse mentions “pañca-pañca-jana”, which the Sānkhya philosophers translate as “the five groups of five”, meaning twenty-five. In this way, they conclude that the word “pañca-pañca-jana” refers to the description of 25 elements given by the atheistic Kapila.

To this, Vyāsadeva answers: na sankhyopasangrahād api nānā-bhāvād atirekāc ca. Even if we were to consider the expression pañca-pañca-jana in the verse as meaning “five groups of five”, it doesn’t match the Sānkhya theory, because the number exceeds the Sānkhya counting and because the groups don’t correspond to the disposition of the elements in the living entities.

As mentioned, the counting of material elements given by Lord Kapila in the original Sānkhya philosophy doesn’t follow the idea of five groupings of five. There are five gross elements, five subtle elements, four internal senses, five senses for gathering knowledge, five outward organs of action, plus time. The counting is thus 5+5+4+5+5+1.

In the atheistic Sānkhya philosophy, the counting also doesn’t follow five groups of five. There are five subtle sense objects, five knowledge-acquiring senses, five working senses, and five material elements, but the other five don’t form a group. Their counting is thus 5+5+5+5+1+1+1+1+1.

In this way, in both philosophies, it is accepted that the disposition of material elements in each living entity does not match the idea of the five groups of five.

Another inconsistency is that the verse describes the meditator, who is an immortal soul, meditating on the Supreme Brahman, in whom everything rests, including both the ether element and the pañca-pañca-jana. In this way, even if we accept that pañca-pañca-jana means “five groups of five”, the verse mentions two other elements (the immortal soul and ether), which are not included in the pañca-pañca-jana grouping mentioned in the verse.

Not only that, but the ether element (ākāśa) is counted as one of the five mahābhūtas, or gross elements, by the Sānkhya system. Therefore, if one argues that the expression “pañca-pañca-jana” in the verse describes the 25 elements of the Sānkhya system, why is it that the verse mentions the ether element again, as being something apart? The obvious answer is that the Bṛhad-āraṇyaka Upaniṣad 4.4.17 doesn’t speak about the 25 elements of the Sānkhya system at all. Pañca-pañca-jana means something else.

Even if, for the sake of argument, we were to accept pañca-pañca-jana as meaning five groups of five, still the verse would not describe 25 elements, but a total of 27, since the verse describes the pañca-pañca-jana, plus the meditator, plus the element ether, all of which rest on the Supreme Brahman.

In this way, it becomes absolutely clear that the verse does not describe the 25 elements of the Sānkhya philosophy at all. Sānkhyaites misinterpret it in a strained attempt to support their doctrine.

There are other enumerations of elements accepted in the Vedas. According to how the counting is done, one can come to a total of seven, six, four, seventeen, sixteen, eleven, or nine elements, and all these classifications are considered correct by the Lord, who explains (SB 11.22.19-24):

“According to some philosophers there are seven elements, namely earth, water, fire, air and ether, along with the conscious spirit soul and the Supreme Soul, who is the basis of both the material elements and the ordinary spirit soul. According to this theory, the body, senses, life airs and all material phenomena are produced from these seven elements.

Other philosophers state that there are six elements — the five physical elements (earth, water, fire, air and ether) and the sixth element, the Supreme Personality of Godhead. That Supreme Lord, endowed with the elements that He has brought forth from Himself, creates this universe and then personally enters within it.

Some philosophers propose the existence of four basic elements, of which three — fire, water and earth — emanate from the fourth, the Self. Once existing, these elements produce the cosmic manifestation, in which all material creation takes place.

Some calculate the existence of seventeen basic elements, namely the five gross elements, the five objects of perception, the five sensory organs, the mind, and the soul as the seventeenth element.

According to the calculation of sixteen elements, the only difference from the previous theory is that the soul is identified with the mind. If we think in terms of five physical elements, five senses, the mind, the individual soul and the Supreme Lord, there are thirteen elements.

Counting eleven, there are the soul, the gross elements and the senses. Eight gross and subtle elements plus the Supreme Lord would make nine.”

As you can see, the counting of the material elements in the Vedas is quite flexible, and there are different ways to do it. However, nowhere in the scriptures is there a description of a counting of 27 elements. Therefore, it’s clear that the verse describes something else, and the interpretation of pañca-pañca-jana meaning five groups of five is just an artificial attempt to give a forced interpretation to it.

Sūtra 1.4.12 - Five pañca-janās don’t mean five groups of five

prāṇādayo vākya-śeṣāt

prāṇādayaḥ: prāna, and the rest; vākya: of the statement; śeṣāt: because of the following passage.

The five units described in the passage are prāna and the rest, as mentioned in the subsequent verse in the passage.

Commentary: If pañca-pañca-jana does not mean five groups of five, or 25 elements, what does it mean? Vyāsadeva answers with prāṇādayo vākya-śeṣāt: It refers to the five units described in the subsequent verse of the passage from the Bṛhad-āraṇyaka Upaniṣad.

Bṛhad-āraṇyaka Upaniṣad 4.4.17 mentions the pañca-pañca-jana and 4.4.18 mentions what it means:

prāṇasya prāṇam uta cakṣuṣaś cakṣur uta śrotrasya śrotram manaso ye mano viduḥ, te nicikyur brahma purāṇam agryam

“Those who know the prāṇa of the prāṇa, the eye of the eye, the ear of the ear, the food of food, and the mind of the mind know this supreme and primeval Brahman.” (Bṛhad-āraṇyaka Upaniṣad 4.4.18)

As we can see, the expression pañca-pañca-jana does not refer to “five groups of five” but instead describes the “five pañca-janas”, which are prāṇa, the eye, the ear, food, and the mind. Vyāsadeva refers to the group using the word prāṇādayo, “prāna, and the rest”.

There is thus a group of five units called the pañca-jana, and when they are counted together, they become the five pañca-janas. This follows a similar logic to when we say “the seven saptarṣis”. There is a group of stars called the saptarṣi (Ursa Major), which is composed of seven stars. Each of these stars is inhabited by a great sage. In this way, the saptarṣi refers both to the seven stars and the seven sages.

When we want to refer to the group, we say “the saptarṣi”, and when we want to refer to each of the seven stars or each of the seven sages, we say “the seven saptarṣis”. The word “saptarṣi” can be translated as “seven stars” or “seven sages”, but when we say “the seven saptarṣis”, it doesn’t mean that there are seven groups of seven stars or 42 sages.

This particular Sanskrit construction is explained by Pāṇini (Aṣṭādhyāyī 2.1.50) where he mentions: dik-sankhye samjñāyām, “Words indicating direction or number may be compounded with another word in the same case.”

In this way, the whole section of the Bṛhad-āraṇyaka Upaniṣad doesn’t at all mention the material elements, but describes a type of meditation where one meditates on the Supreme Brahman, which is the origin of the ether element, the vital air, the eye, the ear, food, and the mind.

This shows how it’s important to always consider the context of the verses preceding and following a passage before jumping into an interpretation, even if it appears to make sense. Otherwise, we can commit elementary mistakes, just like the Sānkhya philosophers in this case.

Sūtra 1.4.13 - The two recensions of the Bṛhad-āraṇyaka Upaniṣad

jyotiṣaikeṣām asaty anne

jyotiṣā: by the word jyotiṣ (light); ekeṣām: in another recension of the Upaniṣad; asaty: being absent; anne: the word anna (food).

In another recension of the text, the word jyotis is found, while the word anna is absent.

Commentary: An objection could be raised to the explanation offered to the last sūtra: The word anna (food) is included in the Madhyandina recension (version) of the Bṛhad-āraṇyaka Upaniṣad, but not in the Kaṇva recension. Verse 4.4.18 in the Kaṇva recension thus lists only four items (prāṇa, eye, ear, and mind) instead of five. This appears to break the logic of the explanation of the pañca-pañca-jana as meaning the five objects.

To this, Vyāsadeva answers: jyotiṣaikeṣām asaty anne. Even though the word anna is missing in the Kānva recension, the word jyotiṣ is added to make the total five.

Śrīla Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa explains that the word jyotiṣ is mentioned in verse 4.4.6 in the words tad devā jyotiṣām jyotiḥ: “The demigods worship Him, the light of lights.”

Because of the context, when the Kaṇva recension mentions the group of five and then mentions only four items, the item described in the previous verse should be added. In this way, the verse in the Kaṇva recension reads:

“Those who know the prāṇa of the prāṇa, the eye of the eye, the ear of the ear, the light of lights, and the mind of the mind know this supreme and primeval Brahman.”

In any case, the total remains five, be it prāṇa, eye, ear, food, and mind, or prāṇa, eye, ear, light, and mind, and thus the explanation of the pañca-pañca-jana remains consistent.

Exercise

Now it’s your turn. Can you answer the following arguments using the ideas from this section?

Opponent: “In the Bṛhad-āraṇyaka Upaniṣad (4.4.17) it is said: yasmin pañca-pañca-janā ākāśāś ca pratiṣṭhitāḥ, tam eva manye ātmānam vidvān brahmāmṛto ’mṛtam: “I, who am immortal spirit, meditate upon the Supreme Brahman in whom ākāśa and the pañca-pañca-janā rest.”

Here arises a doubt: what is the meaning of pañca-pañca-janā? The natural conclusion is that it must refer to the twenty-five elements of the Sānkhya system, because this construction indicates ‘five groups of five,’ which perfectly fit the twenty-five tattvas of Kapila’s philosophy. The Sānkhya system lists twenty-five principles: puruṣa, prakṛti (material nature), mahat, ahankāra, five tanmātras, five bhūtas, five jñānendriyas, five karmendriyas, and manas. The Upaniṣad mentions pañca-pañca (five times five), so the numerical agreement cannot be accidental.

In this way, it is reasonable to interpret the expression “pañca-pañca-janā” in Bṛhad-āraṇyaka 4.4.17 as referring to the twenty-five principles of the Sānkhya philosophy. The Vedic revelation thus corroborates Kapila’s enumeration of tattvas as the basis of creation. Moreover, this interpretation resolves the problem of reconciliation: the Sānkhya tattvas are the substratum in which ākāśa and the other elements rest, and therefore it is proper for the Upaniṣad to speak of them here. Thus, the Vedānta and Sānkhya do not conflict, since Vedānta confirms the 25 elements in the Sānkhya doctrine.”

Description: The Sānkhyite sounds diplomatic in arguing that there is no reason for conflict, while in reality attempting to impose his doctrine. This is similar to a thief who assures his victim that there is no need for a fight, provided the victim surrenders everything peacefully.

He uses a kind of indirect straw-man argument, forcing a meaning onto the verse of the Upaniṣad that the text never intended, and then treating that imposed meaning as evidence. In this way, he constructs an artificial agreement between the Upaniṣad and Sānkhya. Defeating his argument passes through establishing the proper interpretation of the passage. Once the correct meaning is established, the Sānkhya interpretation collapses, since it rests on a projected meaning rather than the true teachings of the text.

You can also donate using Buy Me a Coffee, PayPal, Wise, Revolut, or bank transfers. There is a separate page with all the links. This helps me enormously to have time to write instead of doing other things to make a living. Thanks!

« Vedānta-sūtra: The Govinda-bhāṣya of Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa