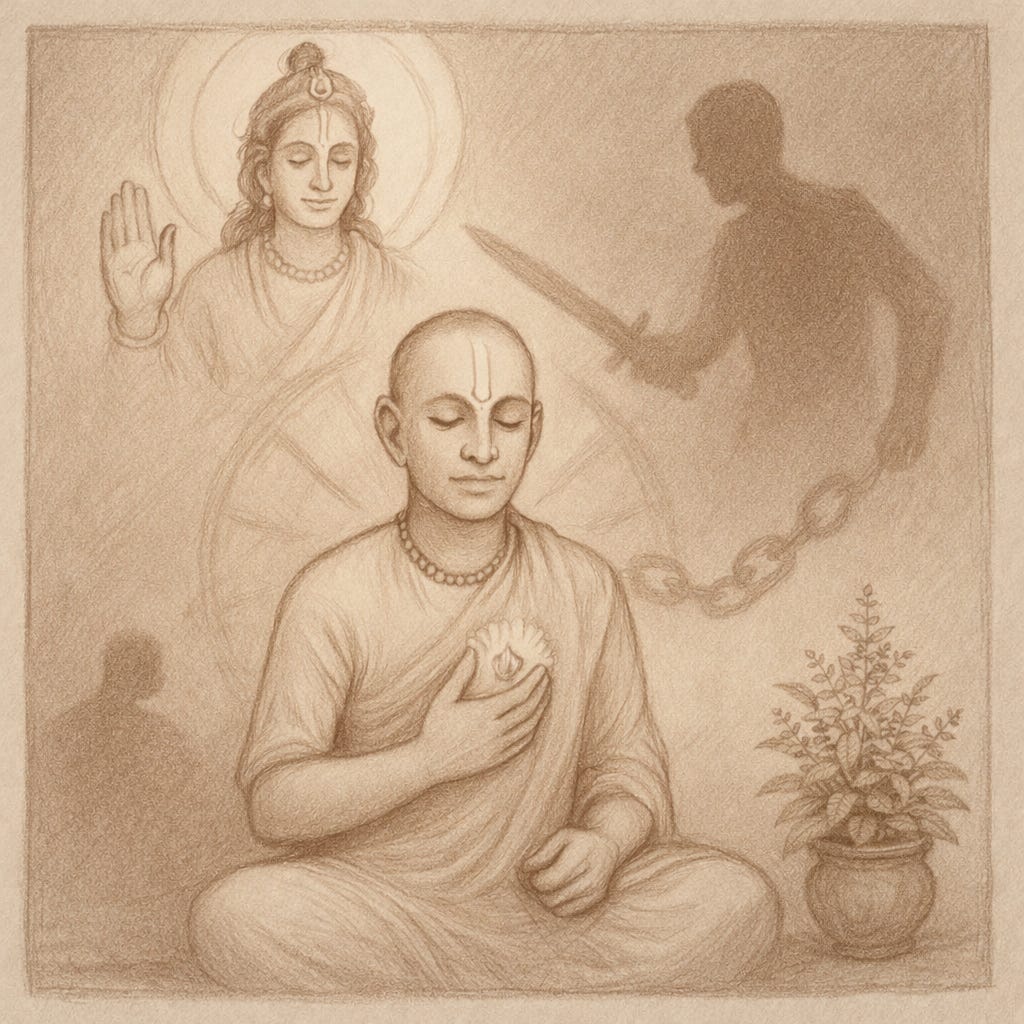

Forgiveness breaks the cycle of conditioned life

We hear that this is a spiritual society, Mahāprabhu’s movement, etc., and we can ask ourselves how cases of abuse and other serious problems can happen in Kṛṣṇa’s own house.

« Things I Wish Someone Had Taught Me When I Started Krishna Consciousness

Forgiveness breaks the cycle of conditioned life

It’s already not easy to accept cases of corruption and abuse in general society, seeing the way politics and dictators abuse their positions, but it becomes even more intolerable when we see these happening in a spiritual institution. Spiritual leaders are supposed to embody humility, purity, integrity, and other good qualities, but sometimes we see people falling short of these ideals and performing activities that would be condemnable even by secular standards. We feel betrayed, shocked, disgusted.

Seeing this, some take to social media, taking the mission of exposing the wrongdoings of such leaders, exposing their deviations, as well as those of others who cooperated with or overlooked them. It may seem like a good deed at first, fighting for justice, but there is a serious downside to that, small letters in the contract that we may fail to notice.

It happens that by taking this role, one becomes bound to follow all actions of the people they are trying to expose, constantly meditating on them. Just as our consciousness becomes uplifted by hearing and meditating about the activities of Kṛṣṇa and His pure devotees, it becomes degraded by meditating on the faults of the bad apples. This constant meditation makes them our constant companions and takes the joy of spiritual life away, covering our devotion with heaps of undesirable moss. We then look back, after many years, and wonder where our enthusiastic and blissful young selves went, where did we get lost on the path. Worse still is that in this process of uncovering faults, we may mistakenly accuse some honest person, which creates yet another set of complications.

Yet another dimension to take into consideration in this issue, however, is described in the passage with the meeting of Parīkṣit Maharaja with Kali and Dharma (in the form of a bull), described in the first canto of Srimad Bhagavatam.

This perspective is not suitable for persons in a position of responsibility, who have the duty of protecting others from harm, which implies somehow confronting wrongdoers, but it can be suitable in situations where we are not directly involved, and there is not much we can personally do. Often, our role in a situation is to just understand the truth, support the victims, and passively stop supporting people who did wrong, not to take direct action. Just as in most cases in ordinary law, we depend on the police and other competent authorities to go after criminals, and are not supposed to take justice into our own hands.

There are also cases when we are the ones harmed, and we have to deal with the feelings of anger and frustration that such an experience produces. In such cases, this knowledge can help us understand things from a higher perspective.

The meeting of Parīkṣit and Dharma

When Parīkṣit came to the scene, Kali was beating the bull. Although the situation was quite obvious, Parīkṣit addressed the bull, trying to get a testimony proving the guilt of Kali, instead of immediately assuming his guilt based on just appearances. This makes the point that we should control our emotions and first examine a situation carefully before taking action.

However, the bull refused to directly accuse Kali, speaking instead in a cryptic way, as if not sure of the cause of his suffering. Understanding the deep meaning of the bull’s words, Parīkṣit replied:

“O you, who are in the form of a bull! You know the truth of religion, and you are speaking according to the principle that the destination intended for the perpetrator of irreligious acts is also intended for one who identifies the perpetrator. You are no other than the personality of religion. Thus it is concluded that the Lord’s energies are inconceivable. No one can estimate them by mental speculation or by word jugglery.” (SB 1.17.22-23)

At first, this passage doesn’t seem to make much sense. It appears that it implies that if a victim reports the perpetrator, asking for justice, one is entitled to receive the same punishment reserved for the criminal. However, when we study it attentively, this cryptic passage from the Srimad Bhagavatam reveals some very profound truths about the law of karma and its implications.

When a person kills another, who is the culprit? Would it be the assassin, because he was the one pulling the trigger? Would it be the victim himself, since he was receiving the results of his past actions? Would it be the revolver, since without a weapon, no murder would take place? Would it be the three modes of material nature that moved people in this direction? Would it be the material nature itself, since it is in control of the three modes? Maybe it’s just chance, and there is no culprit at all?

Although in one sense everything that happens to us is our own fault, since it’s the result of our own past actions, the criminal who pulls the trigger is also to blame. He had the choice of pulling the trigger or not, and still, he did it. If he were not a culprit, he would not be subjected to future punishment. So, in one sense, the killer is an instrument for the realization of the past karma of the person who is killed, but at the same time, he is guilty. How does it work?

Karma works in a very mysterious way. It puts face-to-face a person who is about to commit a crime and someone who has done a similar thing in the past. At the same time, the killer is the instrument of the realization of someone’s past karma, but on the other hand, he is also an individual who has a choice. If he is able to control his mind and throw away his weapon, nobody will die at that time. Because there is free will, when he takes the wrong path and kills, he becomes implicated in the reactions to such a heinous act.

Once one commits violence or harms others in any other way, one becomes bound to the results of this action, and for this, there is no escape. One may escape punishment by the ordinary justice system, but there is no escape for the universal system overseen by Yamarāja. There is, however, an important choice to be made by the victim and other persons affected, which is important to understand.

Revenge keeps us bound to the aggressor

One who is envious and propense to harm others may eventually end up in a situation where he or she has the possibility of killing someone, and the one who did a similar thing in the past is put into the opposite role. The central point is that the law of karma works in a circular way. We may perform a certain action, like violently attacking someone. The person then desires revenge, and at a certain point, in some future life, the roles are reversed. We become the victim, and the victim becomes the aggressor. We then desire revenge, and in some future life, the roles are switched again. We can see that it becomes a loop. In fact, we have been caught in this circle since time immemorial, sometimes being in the position of the aggressor, sometimes in the position of the victim.

Someone who is a victim of violence has the right to desire justice. What we fail to consider, however, is that to receive justice, we will have to stay in this material world to receive it. More than that, to see the perpetrator’s suffering, we will have to be there, which means take our next birth close to the person who did us wrong. Depending on how deep our desire for revenge is, we may even become the wife, husband, or child of the person who harmed us, a position where we can surely cause a lot of suffering and get our revenge. The question is, however, if that’s what we want. The desire for revenge put us on this path of taking another birth in this material world to get it.

That’s why it is said that “the destination intended for the perpetrator of irreligious acts is also intended for one who identifies the perpetrator”; both have to remain here, one to receive the results of his action and the other to get justice. Therefore, a sage who aims to get free from this material world is advised to tolerate the results of his past karma without becoming disturbed. By forgiving, we break the circle. We suffer the reaction to something we did in the past, but without the desire for revenge, we don’t become entitled to be in the reverse position in the future. Thus, we become free. Christ explained this higher principle when he spoke about turning the other cheek in his Sermon on the Mount. This is actually an important point to understand, because that’s one of the tests we have to pass to be able to go back to Godhead. Revenge, or even the desire for justice, is one of the attachments that strongly bind us to this material world. Justice comes automatically, without one having to ask, but we need to renounce the desire to control the process.

There is thus a delicate balance between protecting ourselves and our dependents from harm and getting caught in the cycle of revenge, sometimes taking the role of the victim and sometimes of the aggressor. While it’s perfectly natural to desire justice when we suffer some wrongdoing, when we want to take revenge into our hands, we have to stay in the material world to get it. It’s better to bring the case to the proper authorities and the legal system and let them get the wrongdoers punished (or not) without us getting directly involved in it. In any case, even if one escapes the institutional or legal system, he will not escape the law of karma; therefore, we can make the decision to move on.

Yet another dimension

Yet another dimension to this question is that the spiritual process of Kṛṣṇa Consciousness is practically the only process that allows one to factually change his mentality and behavior and become purified. There is no sin that is great enough not to be forgiven when one sincerely adopts the process of devotional service. Vālmīki was a great thief and killer, but after chanting the name of Rama became completely purified and was able to write the great epic Ramayana.

There are also cases of sadhus who start on the path, fall down at some point, but later continue with renewed strength, like in the case of Bilvamangala Thākura, who was practicing since childhood, having taken birth in a family of brāhmanas, fell down with a prostitute, but later went back to the path much more determined and eventually became one of our most revered ācāryas.

Similarly, one can start his life in a family of meat-eaters, start practicing Kṛṣṇa Consciousness later, fall and commit mistakes at some point, resume on the spiritual path with renewed enthusiasm, humbled by his past mistakes, and in the end become a saintly person, just like in the cases of Vālmīki or Bilvamangala Thākura. There is always a chance for redemption and forgiveness, although it is still up to the individual to take it or not.

Naturally, if one is abusing his position, that’s a different story, but advanced devotees should not be judged by mistakes in the far past if they were able to reform themselves and have been seriously following the spiritual path since then.

As mentioned by Bhīṣmadeva in his discourse to King Yudhiṣṭhira before abandoning his body, one who sees good qualities in others gradually develops their good qualities, while one who criticizes others gradually absorbs their sins and vices. If one is in a position of power and abuses his position, he will certainly be punished, be it directly by the Lord or by the forces of nature. There is already a system of universal justice in place from which no one can escape.

« Things I Wish Someone Had Taught Me When I Started Krishna Consciousness

You can also donate using Buy Me a Coffee, PayPal, Wise, Revolut, or bank transfers. There is a separate page with all the links. This helps me enormously to have time to write instead of doing other things to make a living. Thanks!