How does the original text of Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa look?

it is natural that when we encounter a translation, interpretation, or commentary of a Sanskrit work, we wonder what was written in the original.

« Vedānta-sūtra: The Govinda-bhāṣya of Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa

« Sutra 1.1.1 - athāto brahma-jijñāsā (Beginning of the topic)

How does the original text of Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa look?

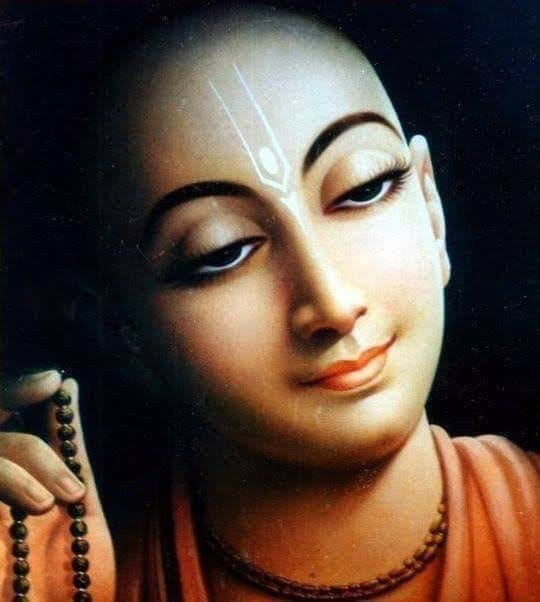

As in other works from our previous ācāryas, the whole commentary of Śrīla Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa in the Govinda-bhāṣya is written in Sanskrit prose, with verses from different scriptures quoted inside the text:

१. ब्रह्मजिज्ञासाधिकरणम्

इत्येवं स्थिते ब्रह्मजिज्ञासाधिकरणं तावत् प्रवर्तते।

यो वै भूमा तत् सुखं, नान्यत् सुखम् अस्ति। भूमैव सुखं, भूमा त्वेव विजिज्ञासितव्यः इति।

आत्मा वा अरे द्रष्टव्यः श्रोतव्यो मन्तव्यो निदिध्यासितव्यो मैत्रेयी इति च श्रूयते।

निदिध्यासितव्यो जिज्ञासितव्यः इति भवति संशयः।

अधीतवेदस्य पुंसो धर्मज्ञस्य ब्रह्मजिज्ञासा युक्ता न युक्ता वेति

अपामसोमम् अमृताः अभूमा, अक्षय्यं ह वै चातुर्मास्ययाजिनः सुकृतं भवतीत्यादिषु धर्मैर् अमृतत्वाक्षय्य–

सुखत्व–श्रवणान् न युक्तेति पूर्वस्मिन् पक्षे प्राप्ते भगवान् बादरायणो व्यासः प्रारिप्सितस्य शास्त्रस्यादिमं सूत्रम् इदम् अवतारयति—

अथातो ब्रह्मजिज्ञासा॥

This can be romanized following the IAST system, which makes it more familiar to us, but not so much:

1. brahmajijñāsādhikaraṇam

ity evaṃ sthite brahmajijñāsādhikaraṇaṃ tāvat pravartate.

yo vai bhūmā tat sukhaṃ, nānyat sukham asti. bhūmaiva sukhaṃ, bhūmā tv eva vijijñāsitavyaḥ iti.

ātmā vā are draṣṭavyaḥ śrotavyo mantavyo nididhyāsitavyo maitreyi iti ca śrūyate.

nididhyāsitavyo jijñāsitavyaḥ iti bhavati saṃśayaḥ.

adhīta-vedasya puṃso dharmajñasya brahma-jijñāsā yuktā na yuktā veti?

apāma-somam amṛtā abhūma, akṣayyaṃ ha vai cāturmāsya-yājinaḥ sukṛtaṃ bhavatīty-ādiṣu dharmair amṛtatva-akṣayya–

sukhatva–śravaṇān na yukteti pūrvasmin pakṣe prāpte bhagavān bādarāyaṇo vyāsaḥ prāripsitasya śāstrasyādimaṃ sūtram idam avatārayati—

athāto brahmajijñāsā ||

It may sound very unusual for us, but in the original there is also no verse numbering for quotes, since the author presumes that the reader will be familiar with different scriptures. Often, just key phrases or lines are quoted, and not even entire verses. Explicit citation of quotes with standardized numbering (like “Bg 4.34”) as we are used to seeing is a modern convention, adopted to make the texts more accessible.

These conventions adopted by Sri Baladeva in his text make it difficult to follow, since a reader who is unfamiliar with the topics discussed will have difficulty even distinguishing the commentary from the verses quoted.

In this work, apart from the translations of the sūtras themselves, I give the translations and references for the verses quoted by Śrīla Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa, as well as explanations and elaborations of the various ideas included in the text, with the goal of making the content accessible and understandable. However, it is natural that when we encounter a translation, interpretation, or commentary of a Sanskrit work, we wonder what was written in the original. To satisfy this natural curiosity, here is a direct translation of the original commentary from Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa on the first sūtra, which you can check to see how the ideas we just studied are originally explained.

In this example, I just try to keep it as close as possible to the original, translating the commentary, but keeping the quotes in Sanskrit, just as Sri Baladeva includes in the original work, so you can have a feeling of how it looks in the original. All these verses are included in the main explanation, so you can just go back there to find the translations and verse numbers.

Here is the translation of the first sūtra:

1. brahmajijñāsādhikaraṇam

Now the topic of inquiry into Brahman begins. The Upaniṣads declare: yo vai bhūma tat sukham, nānyat sukham asti, bhūmaiva sukham, bhūmatveva vijijñāsitavyaḥ, and also: ātmā vā are draṣṭavyaḥ śrotavyo mantavyo nididhyāsitavyo maitreyi. This gives rise to a doubt: Is inquiry into Brahman necessary or not for a person who has studied the Vedas and who knows dharma?

In references such as apāma somaṃ amṛtā abhūma, and akṣayyaṃ ha vai cāturmāsyajinaḥ sukṛtam bhavati, one hears that immortality, inexhaustibility, and bliss come from ritual actions. Thus, it might seem that inquiry is not necessary. When this objection arises, the great Bādarāyaṇa Vyāsa introduces the opening aphorism of the scripture:

athāto brahma-jijñāsāHere, the words atha and ataḥ indicate sequence and causality. Thus, “atha” implies what follows next, and “ataḥ” signifies a reason; together they justify the appropriateness of the inquiry into Brahman. The construction of the phrase suggests that the inquiry is appropriate for one who has studied the Vedas as prescribed, who has a preliminary understanding of their meaning, and whose mind has been purified through duties such as following the sequence of four āśramas and practicing virtue.

Having thus attained eligibility for the knowledge of truth, such a person, having arrived at this juncture, searches beyond fruitive rituals that result in limited and impermanent results. Brahman, however, is known only through knowledge; He is eternal, infinite, and conscious bliss. He is endowed with eternal qualities such as omniscience, and He is the source of eternal bliss. Therefore, only when one has renounced fruitive rituals does the qualified inquiry into Brahman become appropriate.

One might object: does not mere study of the Vedas already yield such understanding, since the purpose of study is to comprehend their meaning? From that understanding, renunciation and meditation would naturally follow. What is then the need for this fourfold-qualified inquiry? It is answered thus: even from a superficial or indirect understanding of the Vedic meaning, the intellect may deviate due to doubt and misapprehension. Therefore, in order to overcome these obstacles, scriptural study that is accompanied by reasoning must be pursued, for only then does the intellect become firmly established in the ultimate reality.

The point is thus that duties associated with the āśrama stages serve as a means of purification of the mind and are thus limbs of knowledge. As stated in the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad: tam etam vedānuvacanena brāhmaṇā vividiṣanti yajñena dānena tapasānāśakena. Similarly, the Muṇḍaka Upaniṣad says: satyena labhyas tapasā hy eṣa ātmā, samyag jñānena brahmacaryeṇa nityam. Also, the smṛti declares: japyenaiva ca samsiddhyed brāhmaṇaḥ nātra samśayaḥ, kuryād anyan na vā kuryān maitro brāhmaṇa ucyate. Association with one who knows the truth is indeed a cause of knowledge, as seen in the case of Nārada, whose inquiry into Brahman arose through his encounter with Sanat-kumāra. This is also supported by the smṛti: tad viddhi praṇipātena, paripraśnena sevayā, upadekṣyanti te jñānam, jñāninas tattva-darśinaḥ.

Fruitive rituals yield impermanent results, as the Chāndogya Upaniṣad states: tad yatheha karma-cito loko kṣīyate, evam evāmutra puṇya-cito loko kṣīyate. The Muṇḍaka Upaniṣad says: parīkṣya lokān karma-citān brāhmaṇo, nirvedam āyān nasty akṛtaḥ kṛtena, tad vijñānārtham sa gurum evābhigacchet, samit pāṇiḥ śrotriyam brahma-niṣṭham. And the Taittirīya Upaniṣad declares Brahman to be satyam jñānam anantam brahma, and ānando brahmeti vyajānāt.

Brahman is thus endowed with eternal qualities such as omniscience, as the Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad affirms: parasya śaktir vividhaiva śrūyate, svābhāvikī jñāna-bala-kriyā ca; sarvendriya-guṇābhāsam sarvendriya-vivarjitam, asaktam sarva-bhṛc caiva nirguṇam guṇa-bhoktṛ ca; bhāva-grāhyam anidākhyam. As for the nature of true happiness, the Gopāla Upaniṣad states: tam pīṭhastham ye tu yajanti dhīrāḥ teṣām sukham śāśvatam netareṣām.

The rejection of fruitive rituals will be explained in the third section. Thus, having studied the Veda along with its auxiliaries and head portions, and having gained a preliminary understanding of its meaning, one becomes engaged, imbued with the fourfold qualifications: Association with knowers of truth; discernment between the eternal and the non-eternal; disinterest in the non-eternal, and desire to realize the eternal. Here, it cannot be claimed that one has to necessarily practice fruitive activities before beginning inquiry into Brahman, because even those who have performed them may not pursue brahma-jijñāsā if they lack association with self-realized persons. Conversely, even those without ritual background but who are purified through truth and have the company of self-realized persons are seen to pursue it. Nor can it be said that the fourfold qualifications come from understanding the difference between eternal and non-eternal, because this understanding is rare and arises only by receiving instructions from the self-realized. Those who have attained this knowledge follow the path of their teachers and, depending on their stage of commitment, fall into three categories: Those who continue performing actions with commitment are known as sa-niṣṭha; those who act for the welfare of the world, though fully accomplished, are called pariniṣṭhā; those who practice only meditation and remain detached, nirapekṣa. All these ultimately reach the Supreme Brahman, each according to their natural inclination for Brahma-vidyā. This gradation is further elaborated step by step.

One might object, mentioning: oṃkāraś cātha-śabdaś ca dvāv etau brahmaṇaḥ purā, kaṇṭhaṃ bhittvā vinirjātau tena māngalikāv ubhau. If one argues that the learned begin with the word atha in śāstra for removing obstacles, I answer that this is not the case, for the Lord is beyond any fear of obstacles. Indeed, the smṛti says, kṛṣṇa-dvaipāyana-vyāsam viddhi nārāyaṇam prabhum. Yet, even so, due to its inherently auspicious nature, the usage of atha may still be accepted as appropriate, just as the sound of a conch is considered auspicious. By that reasoning, even common usage accepts it in this manner. Therefore, for such a qualified person as Vyāsa, it is indeed appropriate that the inquiry into Brahman follows immediately after. A textual unit without a dot or head may be understood as an independent sūtra, even when read in commentary. But when a passage is marked with two bindus [॥] and a mastaka [the connecting line on top of the letters], it must be interpreted as part of a structured topical unit (adhikaraṇa).

As you can see, the text of Śrīla Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa is very elegant and succinct, but not exactly easy to understand. In this commentary, I try to explain all the philosophy behind the arguments and quotes he uses, so we can go deep into the meaning of the text.

Next: Brahma-jijñāsādhikaraṇam: Exercise »

« Vedānta-sūtra: The Govinda-bhāṣya of Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa