Madhvācārya and the Śuddha-dvaita (purified dualism)

Madhvācārya emphasized the differences between the souls and the Lord, as well as the differences between the souls and matter, between matter and the Lord, and between one soul and another.

« Vedānta-sūtra: The Govinda-bhāṣya of Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa

Madhvācārya - Śuddha-dvaita (purified dualism)

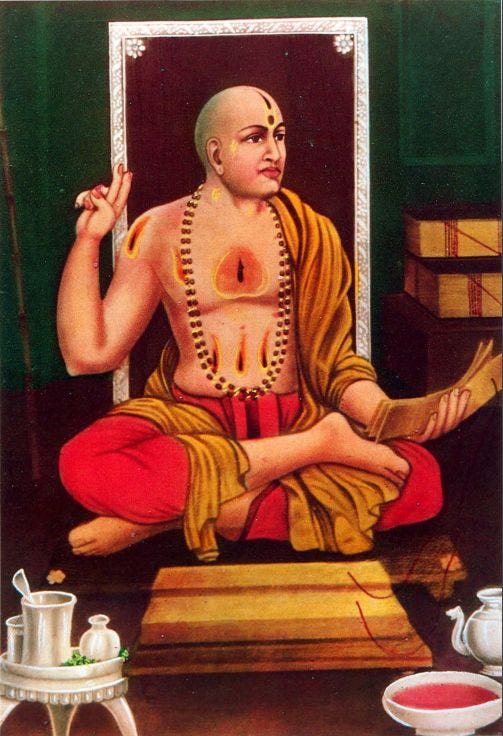

Śrīla Madhvācārya was born as Vāsudeva in 1238, in a village called Pājaka-kṣetra, close to Uḍupi, in South India. His parents performed austerities for twelve years with the goal of getting an enlightened son, and they were finally blessed with the fulfillment of the prophecy that Vāyu, the demigod of the wind, would incarnate on earth and perform many uncommon activities.

On many occasions, their son would show that he was not a common child. Once, when his father had fallen into debt, he gave a bunch of tamarind seeds to the creditor as payment. The creditor initially thought it was child’s play, but when he looked, he saw that the seeds he had in his hand had transformed into gold coins, sufficient to pay the debt. When they visited a nearby village to hear a philosophical discourse on the Purāṇas by a Brāhmaṇa named Śiva, the young boy completed the explanation when the Brāhmaṇa became perplexed upon reaching a difficult passage. Once, when returning from school, he was delayed by the attack of a venomous serpent. Not only did he crush the serpent with great strength using his toe, but jumped the last half a mile of the way back home so as not to be late or worry his mother.

When he concluded his studies at the age of eleven, he went in search of a guru, finding shelter in Acyuta Prekṣa in Uḍupi. He then adopted the name Madhva. At sixteen, he entered the Sannyāsa order and later became known as Madhvācārya.

Although Acyuta Prekṣa was a member of the Advaita school of Śankarācārya, Śrīla Madhvācārya had a cordial guru-disciple relationship with him. Gradually, he developed his own philosophical system, presenting his Śuddha-dvaita philosophy, pointing out the defects of Sankara’s philosophy, and introducing a devotional understanding of the Absolute Truth.

Noticing the philosophical brilliance of his disciple, Acyuta Prekṣa gave him the freedom to teach his philosophy, making him the head of a separate monastery. He also encouraged him to write his commentary on the Vedānta-sūtra, which he later did, writing the Pūrṇaprajña-bhāṣya.

The Vedānta-sūtra brings the conclusions of the Upaniṣads, which were in turn written by Vyāsadeva to teach the philosophical conclusions of the scriptures. The Vedānta-sūtra is thus nothing less than the conclusion of the whole Vedic literature. Since the times of Śankarācārya, the system is that every new philosopher or ācārya who introduces a new philosophical system should write his own commentary on the Vedānta-sūtra, showing that his philosophy is sustained by the Vedic literature. Just like Rāmānujācārya wrote his commentary, sustaining his Viśiṣṭādvaita philosophy, Madhvācārya wrote his own, establishing his Śuddha-dvaitavāda (or Tattvavāda). Later, Śrīla Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa wrote his Govinda-Bhāṣya, firmly establishing the Acintya-bhedābheda-tattva of the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavas.

Madhvācārya spent much of his time discussing philosophy with prominent members of other philosophical schools. With representatives of āstika schools (the ones that accept the Vedas), he would debate based on the Vedānta-sūtras, using references from the sūtras themselves as well as other books within the Vedic literature, combined with impenetrable logic to sustain his views. He also extensively debated with representatives of nāstika schools (the ones that don’t accept the Vedas), such as Buddhists and Jains, to whom he applied strong logic to establish his views.

At that time, the system was that the defeated party would have to accept the philosophy propounded by the victor and become his disciple. Different from what is common nowadays, these scholars were looking for the truth and would thus abandon their old views when presented with something higher. In this way, Madhvācārya made a huge number of disciples from the most intelligent classes.

The Meeting with Vyāsadeva

Śrīla Madhvācārya appears in the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava disciplic succession as a disciple of Vyāsadeva. This is so because although he appeared on the planet thousands of years after Vyāsadeva compiled the Vedas, he was able to personally meet him in Badarīnātha (his hermitage in the Himalayas).

There is the earthly Badarīnātha, a place in the Himalayas where anyone can go, and the celestial Badarīnātha, or Badarīkāśrama, the place where Vyāsadeva lives with Nara-Narāyana and other great sages, which is inaccessible to ordinary humans. The story is that after he wrote his commentary on the Bhagavad-gītā (the Gītā-Bhāṣya), Madhvācārya went to the Himalayas to offer his respects to Vyāsadeva, the original compiler of the book. Staying in the temple of Badarīviśāl in Badarīnātha, he presented his commentary on the Gītā to the Deity. Miraculously, the Lord directly interjected when he read the first line, “I will explain the meaning of the Bhagavad-gītā according to my capacity”. The Lord said that although he had the capacity to reveal the full meaning of the Bhagavad-gītā, he should explain only according to the capacity of his students to understand. In this way, the Lord hinted at the later appearance of Sri Caitanya Mahāprabhu, who would reveal the full meaning of the scriptures.

Madhvācārya decided then to go higher into the Himalayas and personally met Vyāsadeva to get his blessings in establishing his sampradāya. He prepared himself by observing a complete fast and meditating for 48 days, which became just another of his superhuman feats. After warning his disciples that he maybe would not be able to return, he went alone on his journey and eventually reached the celestial Badarīkāśrama, where Vyāsadeva resides surrounded by Ṛṣis. Vyāsa approved his commentary on the Bhagavad-gītā, instructed him on Vedic knowledge, and blessed him to write his commentary on the Vedānta-sūtra and establish the Madhva-sampradāya.

The Śuddha-dvaita philosophy

Certain philosophies are considered dualists because they believe in the existence of another force separated from God, like in the case of the atheistic Sānkhya, where there is the dichotomy of puruṣa and prakṛti, both considered independent forces that interact. According to the Vaiṣnava interpretation, this is incorrect because nothing is independent from God. There is no independent material energy, a devil, or other rival Gods. There is only one Supreme Being who is the source and controller of everything that exists, and there is nothing independent from him. The material world is just part of His external potency, the demigods are His servants, the different souls are part of His marginal potency, and so on.

The philosophy of Śankarācārya is called non-dualism because he rejected the idea of dualism, explaining that there is nothing separated or independent from God or Brahman. However, because people at the time were not able to accept the idea of a personal God, Śankarācārya was forced to limit his explanation, transmitting the idea that there is nothing separate from God, without explaining the existence and interactions of His different energies. In this way, Śankarācārya denied dualism, but He was not able to explain the whole truth, having to settle on the idea that Brahman is everything and we are all Brahman. While this is generally true, because he couldn’t enter into the details that balance the idea, he had to settle into the idea that the material manifestation is false and that we are all God. Indeed, qualitatively we are like God, but quantitatively not.

Rāmānujācārya protested against both dualism and monism, explaining that while everything is God, there are distinctions between His different energies. That’s why his Viśiṣṭādvaita philosophy is called non-dualism with distinctions, or purified monism, since his philosophy sits between both, giving a more balanced and complete view of the absolute truth. Rāmānujācārya explains that God has different energies, emphasizing the difference between sentient and non-sentient, and also between the souls and God. Everything is God, but at the same time, there are distinctions between His different energies. This allowed him to explain both the nature of the cosmic manifestation (as being illusory, but not false), the nature of God as a sentient being who has transcendental qualities, and to emphasize the idea of the relationship between the soul and God and devotional service as a process to revive such a forgotten relationship.

In the process, he also dismissed incorrect interpretations, such as the idea that Kṛṣṇa assumes a material body when He appears in this material world, or that souls have their origin in this material world. Kṛṣṇa is always transcendental, and souls are part of His spiritual, sentient energy and are thus eternally connected with the Lord, although such an eternal relationship may be temporarily forgotten when they come in contact with the non-sentient material energy. By the practice of devotional service, a soul can reestablish such an eternal relationship and thus be reinstated in one’s original position.

As Śrīla Prabhupāda mentions in his explanation of the Śuddha-dvaita philosophy: “Except for Lord Visnu, anything else, either cosmic manifestation or living entities, are not independent but are dependent on the Supreme Lord. The living entities are qualitative representations of the Supreme Lord. The doctrine that man is made after God is accepted by Madhvācārya. The features of man are an exact reflection of the features of the Supreme Lord. He also accepts that the Supreme Lord expands in multi-plenary-portions, as well as separated portions called jiva-tattva. All the jiva-tattvas, or living entities, are eternal associates of the Supreme Lord to render transcendental loving service to Him. The living entities’ knowledge is always inferior or incomplete.”

Madhvācārya emphasized the differences between the souls and the Lord, as well as the differences between the souls and matter, between matter and the Lord, and between one soul and another. In this way, He emphasized individuality, and thus put a nail in the coffin of the misguided idea that we are all one and ultimately all God. No, God is eternally a person, and we are eternally separated from him. I am different from you, you are different from me, and we are both different from the Lord. Just like a son can’t merge back into his father, much less merge into his brothers, we can’t merge into God or merge into each other. We are all eternally separated individuals.

By emphasizing individuality, he reinforced the idea of devotional service to the Lord, which is the central part of his teachings, just like in the case of Rāmānujācārya and all other Vaiṣnava ācāryas. In reality, there is no contradiction between the Viśiṣṭādvaita and Śuddha-dvaita philosophies; they just emphasize different aspects of the same Absolute Truth.

The philosophy of Madhvācārya is called purified dualism because it reconciles the idea of everything being part of the Supreme Lord with the idea of the souls and matter being different from Him. In this way, this philosophy speaks about a personal God and loving relationships between Him and the individual souls, as well as a distinction between the material and spiritual natures. By emphasizing the differences, he positioned his philosophy as diametrically opposite to the monism of Śankarācārya, fighting against the mistaken concept that we are all one.

Often, the philosophy of Madhvācārya is called “Dvaita-Vedānta” in academic circles and translated as “Dualism”. According to the Vaiṣnava interpretation, this is not entirely correct. Dualism is the philosophy of God and the jīvas being different in nature, or of the material nature being separated or independent from God, which is not accepted by any of the Vaiṣnava ācāryas, nor by Śankarācārya. The philosophies of all four Vaiṣnava schools sit in the middle, explaining the delicate balance of God and the jīvas being simultaneously one and different. The four Vaiṣnava schools are thus Suddhādvaita (purified monism), Śuddha-dvaita (purified dualism), Viśiṣṭādvaita (specific monism), Dvaitādvaita (monism and dualism). To this is added the Acintya-bhedābheda-tattva (inconceivable oneness and difference) school of Sri Caitanya Mahāprabhu.

In his Śuddha-dvaita philosophy, Madhvācārya emphasized the distinctions between the souls and the Lord to counteract the monism of Śankarācārya, while at the same time sustaining that the souls are not different or separated from God. His philosophy speaks about five differences:

a) The soul is different from God.

b) One soul is different from another (we are all separate individuals).

c) The soul is different from matter.

d) God is different from matter.

e) One material element or object is different from another.

Although matter and the souls are different from the Lord, they are still completely dependent on Him. Therefore, the Lord is the Supreme. The Lord, on the other hand, does not depend on anyone else; therefore, he is the Supremely Independent Personality of Godhead, who possesses all transcendental qualities and is completely free from material contamination. As Kṛṣṇa explains in the Bhagavad-gītā (9.4), “All beings are in Me, but I am not in them”.

Madhvācārya argues that even at the time of dissolution, both the material energy and the souls remain separate from the Supreme Lord, and there is no possibility of merging with Him at any stage. Although we sometimes say that impersonalists and demons “merge” into the Brahmajyoti, that’s just a figure of speech, since even in the Brahmajyoti the soul continues being a separate entity who is just put in the effulgence of the Lord. The proof is that one can indeed fall from the Brahmajyoti back into the material world.

Another subtle point of Madhvācārya’s philosophy is that although the soul is different from the Lord, the soul is a qualitative representation of the Supreme Lord. In other words, the soul resembles God, although eternally separated from Him and much less powerful. The soul is also different from the Lord in terms of knowledge. The Lord is the possessor of all knowledge, while the knowledge of the soul is inferior or incomplete. Being subordinate and dependent on the Lord, the eternal position of the jīva is one of service. The souls are eternal associates of the Lord, constitutionally bound to offer Him loving devotional service.

Even in this material world, the jīvas are completely dependent on the Lord. We depend on the sanction from antaryāmī (the Supersoul in the heart) not only to perform any material activity but even to think and feel, since the jīva alone can’t do anything. As Kṛṣṇa explains in the Bhagavad-gītā (15.15), “I am seated in the hearts of all living beings, and from Me come memory, knowledge, as well as forgetfulness.”

The nine teachings of Madhvācārya are:

a) Sri Kṛṣṇa alone is the Supreme Absolute Truth, without a second.

b) He is the object of knowledge in all the Vedas.

c) The universe is real, but temporary.

d) The differences between Īśvara (God), the jīva (soul), and matter are real (they are not just due to the influence of māyā as believed by the Māyāvādis).

e) The jīvas are by nature the servants of the Supreme Lord.

f) Jīvas can be divided into two groups: liberated and illusioned. In both states, the jīvas are eternally individuals.

g) Liberation means attaining the lotus feet of the Lord or, in other words, returning to our eternal relationship of service unto Him.

h) Pure devotional service to Kṛṣṇa is the only way to attain this liberation. One should thus not seek liberation, but instead seek devotional service.

i) The truth may be known by pratyakṣa (direct perception), anumāna (inference or logic), and śabda (the Vedic authority).

Madhvācārya also argued that Śankarācārya didn’t emphasize the main aphorism of the Vedas, the Praṇava Omkāra, emphasizing instead secondary aphorisms, such as “tat tvam asi“. In this way, Madhvācārya pointed out that Śankarācārya had presented only partial knowledge about the Vedas, failing to present the whole picture.

This is a point Śrīla Prabhupāda explains in detail in the Teachings of Lord Caitanya:

“Praṇava, or om-kāra, is the chief sound vibration found in the Vedic hymns, and it is considered to be the sound form of the Supreme Lord. From om-kāra all Vedic hymns have emanated, and the world itself has also emanated from this om-kāra sound. The vibration tat tvam asi, also found in the Vedic hymns, is not the chief vibration but is an explanation of the constitutional position of the living entity. Tat tvam asi means that the living entity is a spiritual particle of the supreme spirit, but this is not the chief motif of the Vedānta-sūtra or the Vedic literature. The chief sound representation of the Supreme is om-kāra.” (ToLC 25)

“The principal word in the Vedas – praṇava, or om-kāra – is the sound representation of the Supreme Lord. Therefore om-kāra should be considered the supreme sound. But Śankarācārya has falsely preached that the phrase tat tvam asi is the supreme vibration. Om-kāra is the reservoir of all the energies of the Supreme Lord. Śankara is wrong in maintaining that tat tvam asi is the supreme vibration of the Vedas, for tat tvam asi is only a secondary vibration. Tat tvam asi suggests only a partial representation of the Vedas. In several verses of the Bhagavad-gītā (8.13, 9.17, 17.24) the Lord has given importance to om-kāra. Similarly, om-kāra is given importance in the Atharva Veda and the Māṇḍūkya Upaniṣad. In his Bhagavat-sandarbha, Śrīla Jīva Gosvāmī has given great importance to om-kāra: “Om-kāra is the most confidential sound representation of the Supreme Lord.” The sound representation or name of the Supreme Lord is as good as the Supreme Lord Himself. By vibrating such sounds as om-kāra or Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa, Hare Hare/ Hare Rāma, Hare Rāma, Rāma Rāma, Hare Hare, one can be delivered from the contamination of this material world. Because such vibrations of transcendental sound can deliver a conditioned soul, they are known as tāraka-mantras.” (ToLC 21)

“The Lord has innumerable incarnations, and om-kāra is one of them, in the form of a transcendental syllable. As Kṛṣṇa states in the Bhagavad-gītā (9.17): “Among vibrations, I am the syllable om.” This means that om-kāra is nondifferent from Kṛṣṇa. Impersonalists, however, give more importance to om-kāra than to the Personality of Godhead, Kṛṣṇa. But the fact is that any representational incarnation of the Supreme Lord is nondifferent from Him. Such an incarnation or representation is as good spiritually as the Supreme Lord. Om-kāra is therefore the ultimate representation of all the Vedas. Indeed, the Vedic mantras or hymns have transcendental value because they are prefixed by the syllable om. The Vaiṣṇavas interpret om-kāra, a combination of the letters a, u and m, as follows: The letter a indicates Kṛṣṇa, the Supreme Personality of Godhead, the letter u indicates Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī, Kṛṣṇa’s eternal consort, and the letter m indicates the living entity, the eternal servitor of the Supreme Lord. Śankara has not given such importance to om-kāra. But such importance is given in the Vedas, the Rāmāyaṇa, the Purāṇas and the Mahābhārata, from beginning to end. Thus the glories of the Supreme Lord, the Supreme Personality of Godhead, are declared.” (ToLC 20)

Next: Sri Caitanya Mahāprabhu: Acintya-bhedābheda-tattva (inconceivable oneness and difference) »

You can also donate using Buy Me a Coffee, PayPal, Wise, Revolut, or bank transfers. There is a separate page with all the links. This helps me enormously to have time to write instead of doing other things to make a living. Thanks!

« Vedānta-sūtra: The Govinda-bhāṣya of Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa