Making sense of the description of Bhū-mandala in the Bhāgavatam

The description of Bhū-mandala in the Fifth Canto is a part of the Bhāgavatam that we usually end with more questions than when we started.

Subscribe to receive new articles by e-mail. It’s free, but if you like, you can pledge a donation:

One of the most difficult to understand aspects of the Śrīmad Bhāgavatam is the description of Bhū-mandala in the Fifth Canto, the huge series of concentric islands and oceans that is supposed to divide the universe into two halves. This is a part of the Bhāgavatam that we usually end with more questions than when we started.

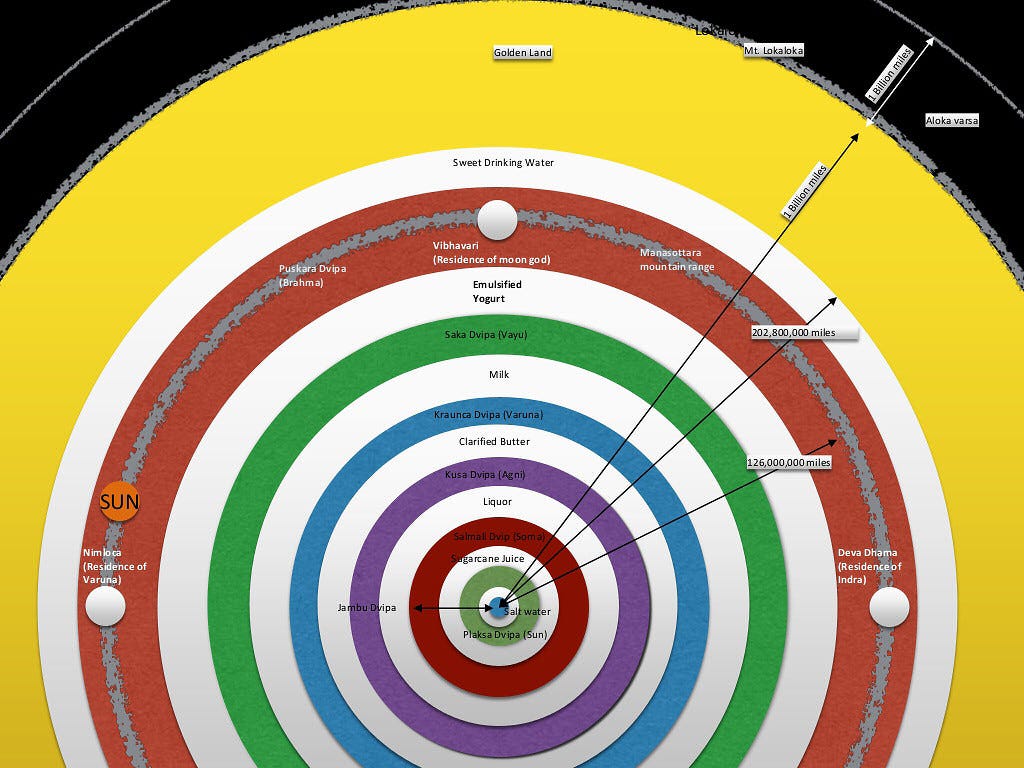

It is described in the Fourth Canto that Priyavrata Maharaja divided the planetary system of Bhū-Mandala into seven concentric islands using his mystic sun-chariot. After the ocean of salt water that surrounds Jambūdvīpa, there are six other islands: Plakṣadvīpa, Śālmalīdvīpa, Kuśadvīpa, Krauñcadvīpa, Śākadvīpa, and Puṣkaradvīpa. Each island is exponentially larger than the previous one, subdivided into separate tracts of land, and surrounded by its own ocean.

How can this description be understood? In his famous letter with his conclusions about the cosmological model of the Vedas, Prabhupāda mentions that,

“The planets have their fixed orbits, but still they are turning with the turning of the great tree. There are pathways leading from one planet to another made of gold, copper, etc., and these are like the branches.”

This describes the idea that both the nine varṣas of Jambūdvīpa, as well as the different tracts of land that form the other islands of Bhū-mandala, appear as separate planets and not literally a sequence of concentric islands around Earth. This is also supported by the analogy of Bhū-mandala being compared to a lotus flower. There are different rings of petals in a lotus, but each ring is constituted of separate petals.

It is also interesting to consider that, by definition, a mandala is not a simple arrangement of concentric rings but a radial–concentric structure where each ring is segmented into discrete, evenly arranged units, like petals radiating from the center of a flower.

Bhū-mandala is often depicted as a series of concentric rings, like this:

However, this is just a simplified model, a visual aid to understand the disposition of the islands. The usage of the term “mandala” and the comparison with a lotus flower make the point that it is, in reality, not a simple sequence of concentric rings, but a much more nuanced structure, composed of planets and subtle passages connecting them, just as Prabhupāda concluded. When it is accepted like that, the emphasis changes from geographical proximity in our observable universe to proximity in terms of accessibility and experience of the respective inhabitants. Bhū-mandala describes thus the intermediate planetary system and the experience of the inhabitants, and not simply a cartographic map.

How can it be that planets that appear distant in our gross reality may appear close together in a higher dimension? Ashish Dalela makes an interesting point in his book Mystic Universe, making the point that distance in the Vedic model is not only geometric, but can also be semantic or hierarchical. In other words, different planets may appear to be far from each other in terms of geometry, and at the same time be close together in terms of similarity and hierarchy, just as different words may appear far from each other in a dictionary but close together in a sentence.

For example, Kṛṣṇa is, in one sense, very distant, situated in Goloka Vṛndāvana, the highest planet in the spiritual sky, inaccessible even for someone able to travel for millions of years at the speed of the mind. In another sense, however, He is inside our hearts and can be seen by persons who have the proper vision. What is this proper vision? Kṛṣṇa is completely pure and spiritual. One who can attain a similar platform, acquiring a pure and spiritual consciousness, can see Him as very near, while someone with a gross, material consciousness sees Him as very distant. Similarly, different planets and other structures of the universe appear closer for people at a similar level of consciousness.

In the Vedic cosmological model, the universe is described as a combination of 14 different planetary systems forming a hierarchical structure. We tend to imagine it as a sequence of disks, one on top of each other, but in practice, it works more like 14 different levels of consciousness. To us, the stars and planets that form these different planetary systems appear spread around the cosmos, and we can’t access any of them, but for their inhabitants, the other planets that compose their respective planetary system appear to be near and connected, just as we have different countries on our planet, connected by roads, shipping routes, airways, etc.

Another way to understand it is to see the universe as an inverted tree, as Kṛṣṇa describes in the Bhagavad-gītā.

Imagine a tree where the branches are invisible. In this case, the leaves and fruits appear to be floating in the air, disconnected from each other. However, when the branches are revealed, we see they are all connected. Similarly, in our gross dimension, we can see only the gross elements of our universe, and thus all planets and stars appear to be very distant from each other, floating in the vastness of space. When the subtle structures are revealed, however, not only do many more structures become visible, but it can also be noted that they are all connected. That’s what Prabhupāda describes as “pathways leading from one planet to another made of gold, copper, etc,” which are like the branches.

In our gross dimension, even the closest stars are light-years away, and according to the theory of special relativity, nothing can travel faster than light. However, both the matter we interact with and the light we see are gross representations of the five material elements. The same elements exist in subtler forms of matter that form the bodies of demigods and other higher beings, as well as their abodes. These subtle forms of matter are not necessarily subject to the same physical laws.

In this way, in the Vedic model, interplanetary travel is completely natural for advanced beings who can travel through the branches that join the different planets, while directly jumping from one leaf to the other, as we try to do in our space exploration programs, is extremely difficult.

The Vedas explain how yogis are capable of traveling all over the universe by elevating their consciousness and thus acquiring bodies suitable to live in the planetary systems they desire. Interplanetary travel thus involves changing the level of consciousness and perception, which leads one to acquire an appropriate body, and not just moving a certain number of physical miles. In this way, the yogī himself (as the combination of soul and subtle body) can easily travel from one planet to another, but his gross body will remain on this planet, left to be cremated or buried.

In conclusion, we receive a gross body on our planet because that’s the level of existence that matched our consciousness at the end of our previous life. With the senses we receive in this body, we can only perceive gross matter, and thus the cosmos appears as an almost empty vastness of space, and other planets and stars are almost unreachable. This also applies to the different instruments we use to study it (such as telescopes), which are made using the same type of gross matter. In this context, traveling using a spaceship is useless because not only does jumping from one leaf to the other take too much time, but also because even if we reach other stars and planets, we can’t interact with the inhabitants there, who will have subtler types of bodies. What is the point of traveling somewhere just to sit in a desert?

The idea of the universe being composed of different dimensions and different species of celestial beings having subtler types of bodies may seem implausible at first, but we have something similar even on our planet. It is well known among different groups of spiritualists that there is a subtle dimension around us that is inhabited by ghosts and spirits. According to the Vedas, ghosts are souls who wander in their subtle bodies, without a gross body. They remain chained to our gross reality because of their attachment, but because they now have a different type of body, they are invisible to us and can’t interact with us or with the objects of our dimension. Although not yet accepted in mainstream science, there are many studies about this. Unless we want to be completely skeptical and believe only in what we can directly see, we have to admit that there are other beings around us that we can’t see and different levels of abodes we can’t perceive. As soon as we admit that, the multidimensional universe of the Vedas starts making sense.

You can also donate using Buy Me a Coffee, PayPal, Wise, Revolut, or bank transfers. There is a separate page with all the links. This helps me enormously to have time to write instead of doing other things to make a living. Thanks! You can also receive the updates on Telegram.