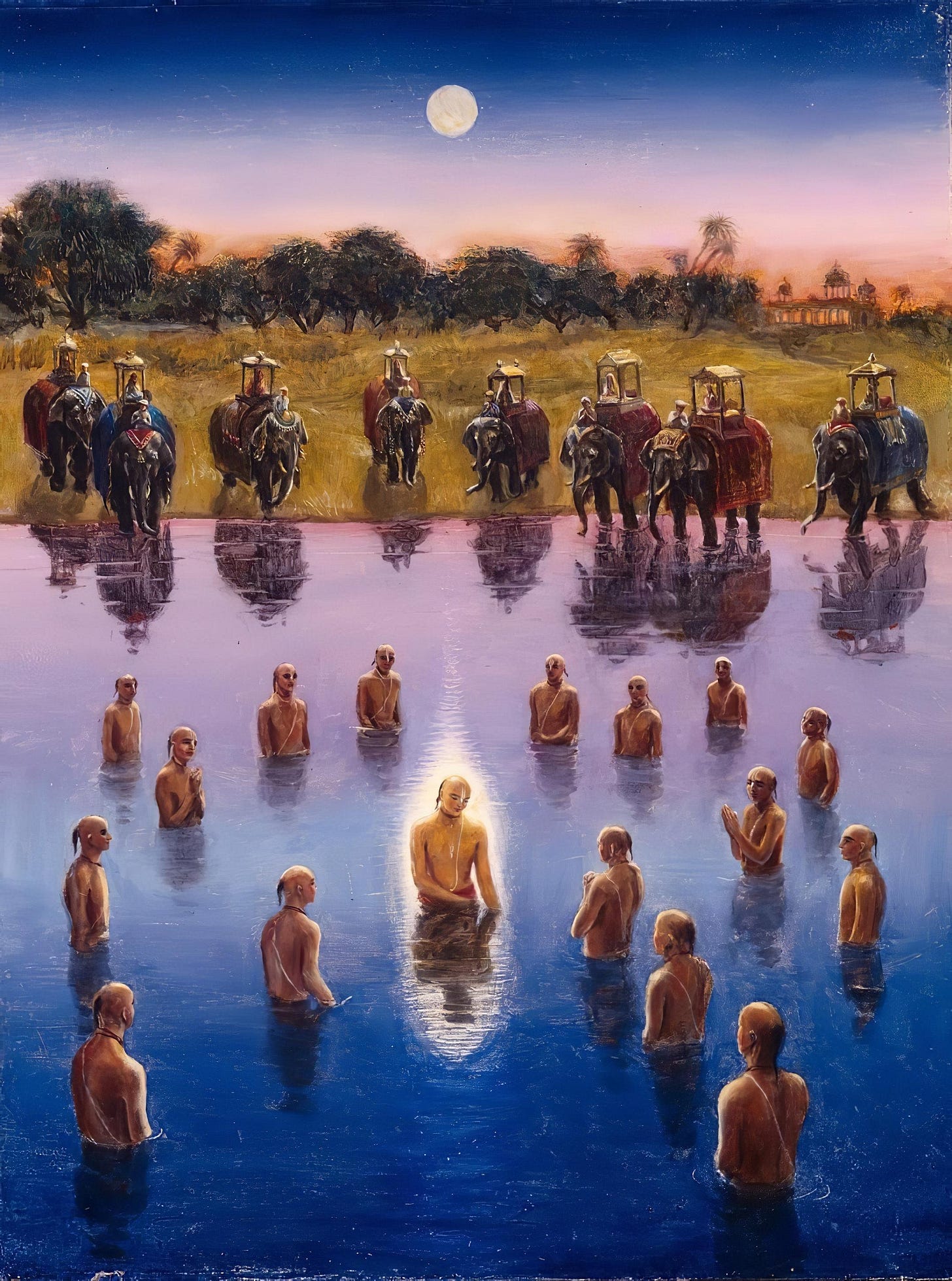

Reflected consciousness

This discussion about the “origin” of the soul is quite complex because it is very difficult for us to think outside of the limitations of material time. The whole discussion is largely misguided

« The ‘Fall’ of the Jīva, as Explained by Śrīla Prabhupāda

Reflected consciousness

This discussion about the “origin” of the soul is quite complex because it is very difficult for us to think outside of the limitations of material time. The whole discussion is largely misguided because, by definition, the soul has no origin, but just an eternal nature that is unchangeable.

Our three immediate prominent ācāryas, Śrīla Prabhupāda, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Thākura, and Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Thākura, share an agreement on the intrinsic nature of the soul as a servant of Kṛṣṇa, and this goes all the way back to Sri Caitanya Mahāprabhu. In fact, all four main Vaiṣnava ācāryas agree on this point, starting with Śrī Rāmānujācārya.

Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Thākura named his main work “Jaiva-dharma”, which can be translated as ‘The Eternal Nature of the Soul‘, again emphasizing the intrinsic nature of the soul as a servant of Kṛṣṇa. As explained by Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu, when all material contaminations are peeled off, this natural love for Kṛṣṇa automatically manifests.

However, we may have real trouble connecting our current consciousness with this perfect intrinsic consciousness. If my intrinsic inclination is to serve Kṛṣṇa, how can my current consciousness be so far from it? To understand this, it’s important to take into consideration that our current consciousness doesn’t have much to do with our original consciousness. Śrīla Prabhupāda explains it by giving the analogy of a dream, which I believe is the best analogy that can be made on this connection.

When I’m inside a dream, I can’t remember who I really am, nor can I remember most facts from my “real” life. I also can’t think straight; everything becomes hazy. Sometimes I may remember something from real life, or even understand I’m inside a dream, but even when this happens, I can still only think inside the constraints of the dream. It’s thus more like dreaming that I’m dreaming than being factually conscious inside the dream.

My sleep also has stages. There is deep sleep, where there is no consciousness, different stages of lighter sleep, the dreaming stage, where I perform activities in my altered dreaming consciousness, and a transitional stage, where I’m almost awakened, but still sleepy and still under the effects of the dream. At this stage, my “real” consciousness is more or less awakened, but I still remember the dream and may easily go back to sleep and start dreaming again.

Similarly, our current consciousness is the product of the combination of the false ego, material mind, intelligence, senses, and finally the gross body, including the brain. All these different layers have different effects, and the final product is what we call consciousness. Similar to the limited consciousness we have inside of a dream, this is not really “us”, but just a temporary delirious stage. As difficult as it may seem to grasp from the position we are now, the goal of life is not to just remain in this dreaming condition, but to gradually peel the material layers and recover our original spiritual consciousness that is currently forgotten.

In the Bhagavad-gītā, Kṛṣṇa explains that the soul is immovable. One meaning of that is that it is not possible to mechanically remove the soul from inside the heart and put it in a different place, as we can do with a material object. A deeper meaning, however, is that the soul is immovable because it never leaves his original position. Whatever the soul is, that’s what he is. There is no possibility of becoming anything else. This eternal nature of the soul is defined by our ācāryas as a position of service to Kṛṣṇa. Losing this position would mean becoming something else, which is impossible since, by definition, spiritual things do not change.

However, the soul may falsely identify with a temporary material consciousness, composed of false ego, mind, intelligence, etc. The soul thus doesn’t become something else, but identifies with it, just like someone playing a game on a computer doesn’t become part of it, although he may identify with the knight on the screen, thinking that he is killing orcs or being killed by them.

This material consciousness is different from the soul, but we identify with it, just like a driver may temporarily identify with a car he is driving, or a gamer may identify with the avatar in the game he is playing, and completely forget he has an existence separated from it. However, different from the driver or the gamer, who can at any moment be easily pushed back to reality, our identification with the temporary material consciousness is much more intimate and long-lasting, and therefore much harder to give up. If one could play a game long enough, one would eventually forget his original identity as a human being and become completely absorbed in the game. His original identity would be thus “lost”, although in reality he is still a human being, and can go back to his original consciousness if he can, somehow or other, become free from the illusory reality of the game.

As in any example, this comparison of the conditioned soul and the gamer has its limitations, but still, the basic principle is similar, since it is based on a false identification. Following this example, we can understand why some of our ācāryas would use the word “lost” when describing the original position of the soul. When something is forgotten long enough, we can say that it is lost, and when something is “lost”, it implies we currently don’t have it with us, but it can still be recovered if we find it. Our true spiritual nature may be thus currently “lost” for us, and as a result, we are disconnected from our original consciousness of love for Kṛṣṇa, but this original consciousness can be restored if we “find” it with the help of a self-realized soul. This understanding is the key to deciphering many intricate philosophical concepts and many apparent disagreements between different spiritual authorities.

In one sense, we were never out of this material world, because what we now call “us” (our current material consciousness, composed of the false ego, mind, intelligence, senses, etc.) is a product of this material world and was never outside of it. When we look from this perspective, we are eternally conditioned, and there was never a time we were out of it. This material identity we identify with was never out of the material world and will never be. The only way for us to become free is by breaking this identification and reconnecting with our original spiritual nature. However, being under the influence of material time, we have, from the material perspective, been disconnected from our eternal nature for so long that it is practically lost to us.

In the true sense, however, when we look from the spiritual perspective, of ourselves as immovable souls, we never left, although our consciousness became somehow entrapped here, identified with the temporary material consciousness. Going back to our original consciousness thus means coming to a stage of Kṛṣṇa Consciousness, and in this purified consciousness, we abandon not just our current material body but also the subtle combination of mind, intelligence, and ego we have been identifying with for so long. Although this process is extremely difficult, it is possible when we follow the process of Kṛṣṇa Consciousness under the guidance of a pure devotee of Kṛṣṇa.

This understanding allows us to reconcile many apparently contradictory ideas. The soul is an eternal servant of Kṛṣṇa, but at the same time, we are here in the material world. We have an intrinsic propensity to serve Kṛṣṇa, but at the same time, we may not have it now. Bhakti is eternally established in the heart, but at the same time, we depend on the mercy of the spiritual master to get it, and so on. When we study the books of Śrīla Prabhupāda, as well as those of our previous ācāryas, with the right understanding, we can understand that there are no contradictions between all these conclusions.

Part of our material conditioning is exactly this propensity of seeing contradictions instead of seeing the underlying principle behind different spiritual principles. For one who is blind, the descriptions of an elephant as being similar to a snake, a fan, a tree trunk, a wall, a rope, and a spear may sound completely contradictory, but a person who can see can immediately understand that these different descriptions are complementary in nature. As long as our intelligence operates under the modes of passion and ignorance, many points of the philosophy will sound contradictory, because under these lower modes, the intelligence operates under material duality, seeing everything as black and white, good or bad, and so on, failing thus to grasp all the delicate aspects of different explanations. Only when we are able to ascend at least to the mode of goodness does our intelligence start to work properly. Apart from that, there is a need to receive the right conclusions from a self-realized soul and have faith in such conclusions. Without following this process, even the greatest celestial sages are incapable of understanding transcendental knowledge.

In his Tattva Sandarbha, Śrīla Jīva Goswami explains that the Vedic literature is written in very esoteric language, and the only way to understand it is by receiving the right conclusions from a self-realized soul and studying the text under this prism. Even when we go to the works of our previous ācāryas, the possibility of misunderstanding is still present, since their books were written in a language and cultural context that is often incomprehensible to us. We then come to the books of Śrīla Prabhupāda, who is the current prominent link of our sampradāya. In these books, we find something that we can clearly understand, and if we accept all the conclusions he gives, we may be able to gradually study all the works of the previous ācāryas and properly understand them.

Becoming free from the false ego

“Although a devotee appears to be merged in the five material elements, the objects of material enjoyment, the material senses and material mind and intelligence, he is understood to be awake and to be freed from the false ego.

The living entity can vividly feel his existence as the seer, but because of the disappearance of the ego during the state of deep sleep, he falsely takes himself to be lost, like a man who has lost his fortune and feels distressed, thinking himself to be lost. When, by mature understanding, one can realize his individuality, then the situation he accepts under false ego becomes manifest to him.” (SB 3.27.14-16)

In these verses, Lord Kapila explains more about the nature of the false ego, details how a person can realize his eternal nature while still living in the material body, and calls our attention to the menace of impersonalism, the last snare of māyā, that can prevent a soul striving for perfection from attaining the ultimate goal. Falling into this trap, the transcendentalist gives up the search for his eternal, original position and settles in a position of pseudo-liberation, still under material conceptions.

The connection between the soul and the material reality is the false ego. The material manifestation is composed of many planets, countries, bodies, and material experiences, and everything is going on more or less automatically because of the influence of the three modes of material nature. There are millions of living beings being born and dying in innumerable universes every second, but it doesn’t at all concern us. However, when the particular material body we call “ours” is under threat, we become terrified. This happens due to our identification with this particular body and its byproducts. Even when we understand we are not the body, we still tend to think we are the mind or the intelligence. This all happens under the influence of the false ego.

The practical effect of the false ego is to create the sense of an identity different from the soul’s eternal identity as an eternal servitor of the Lord. Under the influence of the false ego, one is prepared to accept any position, be it that of a demigod, a human being, a horse, or a cat; any position at all, except his original position as an eternal servant of the Lord.

Under the spell of the false ego, we forget our original identity and become absorbed in lamentation connected with different material situations. Lord Kapila compares this state with the situation of a man who forgets himself while sleeping. While sleeping, one doesn’t stop existing, nor does he go anywhere, but due to the forgetfulness of sleep, he becomes unconscious. While sleeping, one can also identify with illusory situations while dreaming, but these also don’t affect his real existence. Another example given is that a man identifying with his money may think he is lost after losing some money, but this is also due to illusion, since only the money was lost.

These different concepts (of a person losing consciousness while sleeping, identifying with illusory situations while dreaming, and identifying with his money) illustrate how the soul forgets his eternal nature while absorbed in the material world, although one’s original spiritual identity is never lost.

As Prabhupāda explains in his purport to text 3.27.15: “Similarly, when we falsely identify with matter as our field of activities, we think that we are lost, although actually we are not. As soon as a person is awakened to the pure knowledge of understanding that he is an eternal servitor of the Lord, his own real position is revived. A living entity can never be lost. When one forgets his identity in deep sleep, he becomes absorbed in dreams, and he may think himself a different person or may think himself lost. But actually his identity is intact. This concept of being lost is due to false ego, and it continues as long as one is not awakened to the sense of his existence as an eternal servitor of the Lord.”

Only when we finally realize our eternal position in our relationship with the Lord can this false ego be finally given up. At this point, we may still be living in the body, but by not identifying with it, we can be situated in our original, transcendental position.

Prabhupāda explains this point in his purport to text 3.27.14:

“The explanation by Rūpa Gosvāmī in the Bhakti-rasāmṛta-sindhu of how a person can be liberated even in this body is more elaborately explained in this verse. The living entity who has become satya-dṛk, who realizes his position in relationship with the Supreme Personality of Godhead, may remain apparently merged in the five elements of matter, the five material sense objects, the ten senses and the mind and intelligence, but still he is considered to be awake and to be freed from the reaction of false ego. Here the word līna is very significant. The Māyāvādī philosophers recommend merging in the impersonal effulgence of Brahman; that is their ultimate goal, or destination. That merging is also mentioned here. But in spite of merging, one can keep his individuality. The example given by Jīva Gosvāmī is that a green bird that enters a green tree appears to merge in the color of greenness, but actually the bird does not lose its individuality. Similarly, a living entity merged either in the material nature or in the spiritual nature does not give up his individuality. Real individuality is to understand oneself to be the eternal servitor of the Supreme Lord. This information is received from the mouth of Lord Caitanya. He said clearly, upon the inquiry of Sanātana Gosvāmī, that a living entity is the servitor of Kṛṣṇa eternally. Kṛṣṇa also confirms in Bhagavad-gītā that the living entity is eternally His part and parcel. The part and parcel is meant to serve the whole. This is individuality. It is so even in this material existence, when the living entity apparently merges in matter. His gross body is made up of five elements, his subtle body is made of mind, intelligence, false ego and contaminated consciousness, and he has five active senses and five knowledge-acquiring senses. In this way he merges in matter. But even while merged in the twenty-four elements of matter, he can keep his individuality as the eternal servitor of the Lord. Either in the spiritual nature or in the material nature, such a servitor is to be considered a liberated soul. That is the explanation of the authorities, and it is confirmed in this verse.”

As long as we are not prepared to accept our original position, any other identity we may accept will still be under the concept of false ego. When we finally understand we are not the body, nor the mind, nor the intelligence, that we are not part of this material world, but part of the eternal spiritual nature, a last trap is set up by māyā: the idea of being one with the Lord. This allows the soul to accept the idea of becoming free from material contamination without accepting his original position of service to the Lord. As Prabhupāda explains, this is also a form of false ego, making one believe oneself to be something he is not. The result is that instead of reattaining one’s original position in the spiritual planets, the soul can go no further than the pradhāna or the impersonal brahmajyoti, positions from which one can fall back into the material energy.

As Prabhupāda explains, “The Māyāvādī philosophers’ concept of becoming one with the Supreme Lord is another symptom of being lost in false ego. One may falsely claim that he is the Supreme Lord, but actually he is not. This is the last snare of māyā’s influence upon the living entity. To think oneself equal with the Supreme Lord or to think oneself to be the Supreme Lord Himself is also due to false ego.”

The idea of becoming one with the Lord or His associates is also found in several Vaiṣnava apa-sampradāyas. Sakhi-bhekis, for example, still common in Vṛndāvana, believe that one can become one with Kṛṣṇa’s associates, instead of becoming one of their servants. Similarly, cūdā-dhārīs believe they can become one with Kṛṣṇa by imitating His rasa dance. Ativadis, common in Jagannātha Puri, worship Lord Jagannātha while at the same time believing they will ultimately become one with Him. They are all attracted to Kṛṣṇa, but their devotion is somehow misguided and transformed into a desire to become Him, instead of aiming to serve Him.

Other sahajiyā groups adopt a false form of siddha-praṇālī, where one acquires an imaginary relationship with Kṛṣṇa. There is a true siddha-praṇālī, based on reviving our eternal relationship with the Lord by practicing Kṛṣṇa Consciousness in the association of pure devotees, but that is different from the imitation practiced by these groups. This imaginary siddha-praṇālī is just another form of upādhi, an imposed material designation that is under the influence of false ego.

Prabhupāda comments on this in chapter 16 of Nectar of Devotion, when he mentions:

“In this connection, we should be careful about the so-called siddha-praṇālī. The siddha-praṇālī process is followed by a class of men who are not very authorized and who have manufactured their own way of devotional service. They imagine that they have become associates of the Lord simply by thinking of themselves like that. This external behavior is not at all according to the regulative principles. The so-called siddha-praṇālī process is followed by the prākṛta-sahajiyā, a pseudosect of so-called Vaiṣṇavas. In the opinion of Rūpa Gosvāmī, such activities are simply disturbances to the standard way of devotional service.”

Only when we can survive the onslaught of all these misconceptions and keep ourselves on the proper spiritual path coming to us through our Paramparā, can we finally come to understand our real relationship with Kṛṣṇa, finally surpassing the influence of the false ego.

You can also donate using Buy Me a Coffee, PayPal, Wise, Revolut, or bank transfers. There is a separate page with all the links. This helps me enormously to have time to write instead of doing other things to make a living. Thanks!