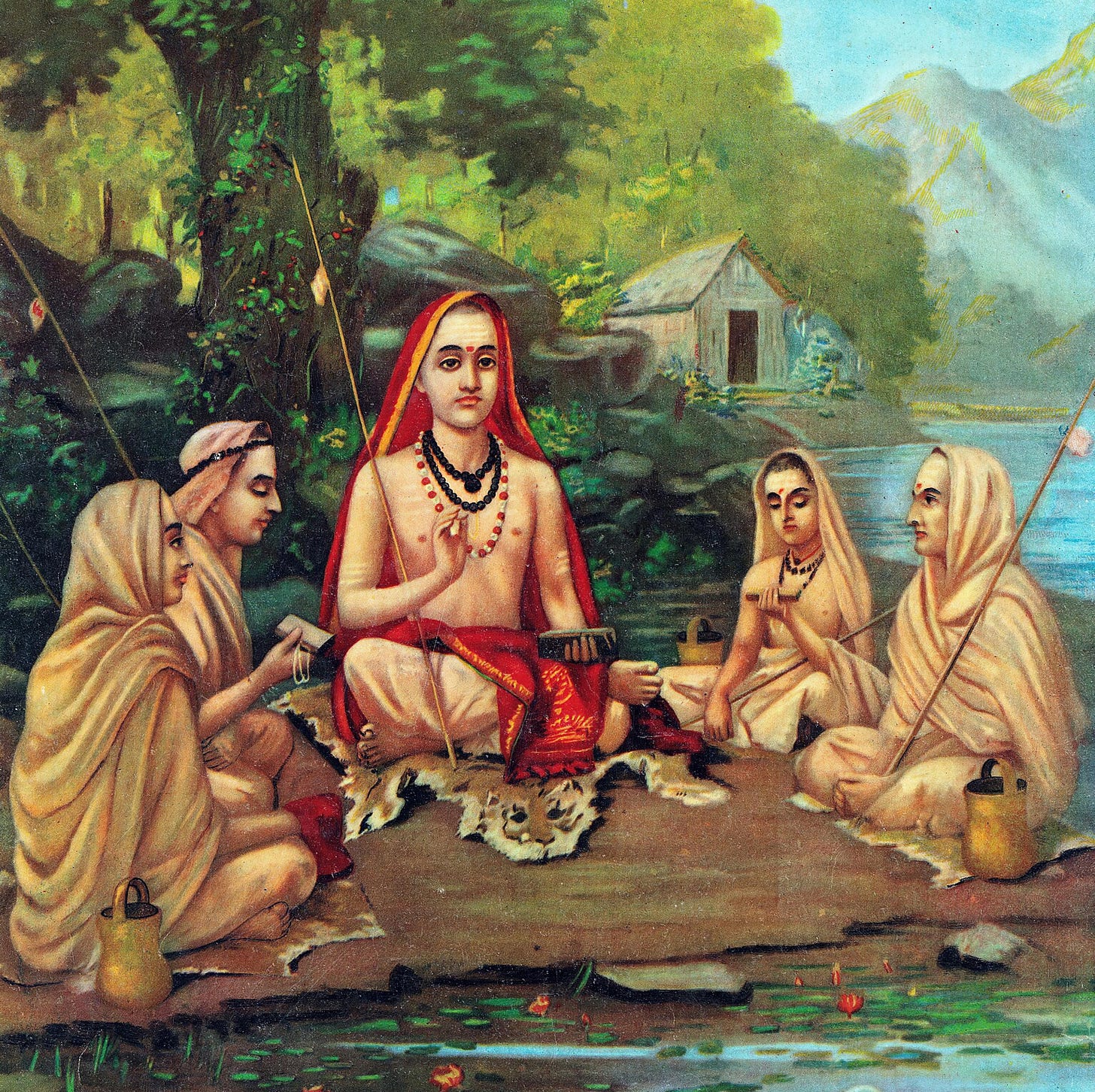

Śankarācārya - Advaita-Vedānta (non-dualism)

The foundations laid by Lord Buddha created the conditions for the appearance of Śaṅkarācārya, who introduced the next step on the spiritual stairway, the Advaita-Vedanta, or non-dualism.

« Vedānta-sūtra: The Govinda-bhāṣya of Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa

The foundations laid by Lord Buddha created the conditions for the appearance of Śankarācārya, who introduced the next step on the spiritual stairway.

The philosophy of Lord Buddha is called Śūnyavāda, or nihilism, while the philosophy of Śankarācārya is called Advaita-Vedānta, or non-dualism. In essence, both philosophies are quite similar. Basically, Buddhism says that the absolute truth is zero, a void where one can find the absence of suffering. Śankarācārya, in turn, says the absolute truth is one, the impersonal, undifferentiated, and qualityless impersonal Brahman, where one can find the end of all the illusory designations of this material world and realize his existence as independent from matter. Philosophically, there is little difference in their conclusions, but the Advaita-Vedānta is based on the Vedas, which opened the door to the reestablishment of the brāhminical culture and allowed the different Vaiṣnava ācāryas who came later to gradually rebuild the correct conclusions of the scriptures by adding the topics that Śankarācārya avoided.

Śankarācārya appeared in the 8th century, about 1,300 years after Lord Buddha. At that time, Buddhism had become the prevalent philosophy in India, and followers of the Vedas were still mostly ritualistic karma-kandis with little understanding of the real purpose of the scriptures. His mission was to reestablish the authority of the Vedas by teaching a philosophy that was similar to Buddhism, but based on the Vedas, especially on the Vedānta-sūtra. With this, philosophers in India returned to the study of the Vedas, which opened the doors for other ācāryas to gradually reestablish the real goal of the scriptures.

It’s well-known that Śankarācārya was an incarnation of Lord Śiva. The Padma Purāṇa, Uttara-khaṇḍa (25.7) mentions:

māyāvādam asac-chāstram, pracchannam bauddham ucyate

mayaiva vihitam devi, kalau brāhmaṇa-mūrtinā

“[Lord Śiva informed the Goddess Durgā, the superintendent of the material world,] ‘In the Age of Kali I take the form of a brāhmaṇa and explain the Vedas through false scriptures in an atheistic way, similar to Buddhist philosophy.’”

In his Jaiva Dharma (chapter two), Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Thākura explains the advent of Lord Śiva as Śankarācārya:

“Paramahamsa Premadāsa Bābājī prostrated himself respectfully upon hearing the name of Śrī Śankarācārya. He said, “My dear sir, always remember this: śankaraḥ śankaraḥ sākṣād ‘Śrī Śankarācārya is Lord Śiva himself.’ Śrī Śankarācārya is the spiritual preceptor of all the Vaiṣṇavas, and for this reason, Śrī Caitanya has acclaimed him as an ācārya, great preceptor. Śrī Śankarācārya is a perfect Vaiṣṇava.

At the time of his appearance, India urgently required a guṇa-avatāra, an incarnation who presides over the material nature, because the spread of the voidistic philosophy of Buddhism had caused India to practically give up the cultivation and study of the Vedas, as well as the practice of varṇāśrama–dharma, the Vedic social system. Nihilistic Buddhism, known as śūnyavāda, directly denies the existence of a personal God, and although hinting at the principle of the jīvātmā, the eternal spirit soul, Buddhism remains in essence anitya–dharma. In those days, the brāhmaṇas had all but forsaken the Vedic religion and converted to Buddhism.

At this historic moment, the extraordinarily powerful Lord Śiva appeared as Śrī Śankarācārya and reinstated the pristine glory of the Vedas by transforming nihilistic Voidism into monistic Brahmanism. This was a spectacular achievement, for which India will always remain indebted to Śrī Śankarācārya. Works in the world may be judged by two standards. Some works are tat–kālika, specific to a particular time, and others are sarva–kālika, for all time. Śrī Śankarācārya’s achievement, which resulted in great good for human society, belongs to the former category. He laid a firm foundation, upon which Śrī Rāmānujācārya and Śrī Madhvācārya later constructed the grand edifice of pure Vaiṣṇava philosophy. Therefore, he is one of the greatest benefactors and historic torchbearers of the Vaiṣṇava religion.”

Śankara’s Life and Teachings

Śrīpāda Śankarācārya appeared in Kalāḍi, a province in the south of India, as the son of a Brāhmaṇa called Śivaguru. He was a prodigious student, learning in just one year what others would take 12 years to learn. At the age of eight, he left home to become a renunciant. He became a disciple of Govindapāda. From him, he learned four maxims from the Upaniṣads that would later become the basis of his philosophy:

“prajñānam brahma” (Brahman is consciousness)

“ayam ātmā brahma” (the Self is Brahman)

“tat tvam asi” (you are that)

“aham brahmāsmi” (I am Brahman)

These four aphorisms are considered the four mahāvākyas (the four great statements) of the Advaita-Vedānta philosophy, and all verses of the scriptures are interpreted according to them. Just like, as Vaiṣnavas, we accept SB 1.3.28 (ete cāmśa-kalāḥ pumsaḥ kṛṣṇas tu bhagavān svayam, “All of the above-mentioned incarnations are either plenary portions or portions of the plenary portions of the Lord, but Lord Śrī Kṛṣṇa is the original Personality of Godhead”) as the paribhāṣā sūtra of the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam and understand the whole book from this prism, Māyāvādis interpret the whole Vedic literature from the prism that everything is Brahman, and we are that Brahman.

These mahāvākyas are general instructions of the scriptures and are not incorrect. Indeed, Brahman (the Supreme Lord) is consciousness, the Self (the Lord) is Brahman, and we are also Brahman (spirit). Also, we are like the Lord (in the sense that we are also spirit and share most of His qualities); none of these passages contradict the idea that we are separated personalities or that we have an eternal relationship of service to the Lord. The difficulty is that Māyāvādis misinterpret and overemphasize these instructions, discarding or misinterpreting the many statements that describe other aspects.

When Sankara was twelve, his guru sent him to Benares to convert the Buddhists there to the path of the Vedas. Buddhism is considered an atheistic philosophy due to its rejection of the Vedas, and thus, Śankarācārya had the mission of bringing them back to theism, accepting the Vedic scriptures. Defeating many great philosophers, he soon attracted many disciples and became known as Śankarācārya. Vaiṣnavas also respect him as a great teacher because of his efforts in bringing people back to the path of the Vedas. We disagree with the Māyāvāda philosophy that his followers created based on his teachings, but at the same time, we understand he had to make a compromise according to the time and circumstances.

The Advaita philosophy

Śankarācārya wrote commentaries on the Bhagavad-gītā and other books, but his most famous work was the Śārīraka-bhāṣya, his commentary on the Vedānta-sūtra, which became hugely popular. According to him, Brahman is the supreme reality, beyond the reach of the senses. Brahman is eternal, formless, and unchanging.

His philosophy is called non-dualism, or monism, because it doesn’t distinguish the supreme Brahman from the individual soul. According to it, both are the same, being the souls just parts of Brahman that become covered by Māyā. According to his philosophy, once this covering is removed, one realizes oneself as one with Brahman.

This brings us to the equivocated Māyāvādī ideas that were later contested by other ācāryas, starting with Sri Rāmānujācārya:

a) God has no form and no activities.

b) We are all God since we are the result of the Supreme Brahman being covered by avidyā, or Māyā.

c) Once the veil of Māyā is removed, we become all one. Outside of the material illusion, there is no individuality.

d) Even though Māyāvādis phrase it in a different way, the practical conclusion of their philosophy is that Māyā is greater than Brahman, since it has the power to put it under illusion.

e) Kṛṣṇa and all His incarnations accept material forms when they descend since all forms and activities exist only under the veil of Māyā.

According to Śankarācārya, Brahman is never transformed, and therefore the material world is mithyā, an illusory appearance of reality. It exists only under the illusion of Māyā. Once the illusion is removed, one understands that there is no material world, just like one may see a rope on the road and, under illusion, take it as a snake, but when the mistake is clarified, we understand that there was never a snake. The existence of the snake was thus always illusory, existing only under the misconception of the rope being a snake. Similarly, according to his teachings, the material world exists only under the illusion created by Māyā. As soon as we can see beyond this illusion, we understand that we are all one with the transcendental Brahman, and in truth, there is no material world.

The question of where this illusion or Māyā comes from is considered unanswerable, and Brahman is considered to be indescribable by words since any description would be covered by the illusion of Māyā.

Becoming free from Māyā, according to him, means renouncing all relationships with the material world, including all forms of “I and Mine” (including wife, children, properties, and so on). Traditionally, the followers of Śankarācārya emphasize renunciation and asceticism, but in modern times, many impersonalists who concoct new philosophies based on his teachings go in the opposite direction, propounding permissive philosophies with quite loose moral standards.

Śankarācārya created a philosophy according to what was necessary to reestablish the Vedas at the time, offering something familiar to the audience, but at the same time one step higher. The problem is that the impersonalist philosophy he composed is not supported in the Vedas, which very strongly support the idea of a personal God and recommend the path of devotion. The verses in the Vedas, and particularly the passages that compose the Upaniṣads, have both direct and indirect meanings, and Sanskrit words can be interpreted in different ways. By cleverly playing with the grammatical rules, as well as suffixes, prefixes, and affixes of the words, he was able to interpret books like the Vedānta-sūtra and the Bhagavad-gītā in ways that suited his philosophy. He, however, didn’t touch the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, because the direct way it explains the process of bhakti makes it practically impossible to misinterpret.

Just to give one example, one of the four mahāvākyas of the Māyāvāda school is “tat tvam asi“, which is often accepted by Māyāvādis as their main mantra, their object of contemplation, a means of realizing their real identity as the Supreme Brahman. They believe that by contemplating the mahāvākyas, studying Vedānta philosophy, and analyzing reality according to this knowledge, one comes to the stage of realizing one’s real nature. When one finally attains it, he sees himself as the Supreme Brahman.

The maxim “tat tvam asi” comes from the Chāndogya Upaniṣad (6.10). There, Uddālaka describes several characteristics of the Supreme Brahman to his son, Śvetaketu, and concludes each explanation with the words “tat tvam asi“. Māyāvādis interpret this passage as meaning “you are that (Brahman)”. Some gurus in the West even translate it as “I am God”. However, this is not the correct interpretation.

“Tat tvam asi“ indicates similarity. For example, when we say “you are like him”, pointing to another person, it doesn’t mean that literally you are him, but that although different individuals, you share similar qualities or characteristics. The soul is the same as the Lord in terms of quality but is different in terms of quantity. The soul is also a separate individual. It’s thus incorrect to interpret tat tvam asi as “you are that”. The correct translation is “You are like that”, indicating that we are like the Lord, although eternally separated as different individuals. Prabhupāda translates tat tvam asi as “you are the same spiritual identity” and as “you are as good as God.”

Being spiritual and transcendental, as good as God, we need to revive our original spiritual identity by the practice of Kṛṣṇa Consciousness, becoming detached from the material body and the material manifestation, just like Kṛṣṇa is. As Prabhupāda explains: “Although sitting in the same body as the individual soul, the Supersoul has no affection for the body, whereas the individual soul does. Therefore, one has to detach oneself from this material body by discharging devotional service.”

Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Thākura comments on the real meaning of “tat tvam asi” in his Jaiva Dharma (ch. 18), where he concludes: “A person who realizes the actual truth of tat tvam asi ultimately attains devotional service to the Supreme Lord and becomes a true practicing brāhmaṇa.”

Māyāvāda

Most of the points in the philosophy of Śankarācārya are valid points explained in the Vedas. In the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, for example, it is mentioned:

vadanti tat tattva-vidas, tattvam yaj jñānam advayam

brahmeti paramātmeti, bhagavān iti śabdyate

“Learned transcendentalists who know the Absolute Truth call this nondual substance Brahman, Paramātmā or Bhagavān.”

The Lord has three aspects that are simultaneously true. For the devotees, he appears in His personal aspect, as Bhagavān, the possessor of all opulences. To the yogis, He appears as the localized Paramatma, and to the impersonalists as the effulgent Brahmajyoti. The Bhagavān aspect is supreme, but all three aspects are part of the same absolute truth. Most of what Śankarācārya did was to explain the Brahman aspect, which sounded familiar to the people of the time, while avoiding the other two.

However, the need to emphasize the impersonal aspect led him to reject the idea of Brahman processing potencies, which in turn leads to the conclusion that the jīvas have no individual existence once separated from matter. This takes the idea of transcendental relationships out of question and thus negates the very nature of the soul, which is love and service to Kṛṣṇa. Māyāvādis accept the ideas of worshiping the deity and chanting the holy names as just temporary processes that one may practice to later realize one is God. Even the guru is seen as just a stepping stone, which one accepts with the idea of later rejecting after attaining a certain stage of realization.

The idea that Brahman has no potencies also leads to the conclusion that the material world is ultimately false, just as the snake on the road, seen in place of the rope. We disagree with this idea, arguing that being true, Brahman can’t produce something false, but inside of Māyāvāda philosophy, this is the only way to explain how a changeless Brahman, that has no potencies, can produce the material manifestation. They conclude that the material manifestation doesn’t exist outside the influence of Māyā, or illusion. Brahman thus is not transformed by creating it, since the material world ultimately doesn’t exist. Brahman is thus formless and qualityless, and all forms, qualities, activities, etc., exist only under the realm of illusion.

This conclusion, in turn, leads to the most terrible belief of the Māyāvāda philosophy: Their conclusion that when Brahman comes to the material world as an incarnation, He assumes a material form. According to the Māyāvādis, Kṛṣṇa had a material body and was acting under the material mode of goodness while executing His pastimes, just as a conditioned soul. Although a Māyāvādi will deny it and try to phrase it in a different way, the practical implication of this conclusion is that Māyā is greater than God, because it can overpower Him.

This idea that the form of the Lord is material was defined by Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu as the most horrible philosophy, and all Vaiṣnavas protested strongly against it. That’s why we call it the Māyāvāda philosophy, calling off the falsity of their claim that the transcendental form of the Lord is material. Māyāvādis, however, don’t call themselves as such. If asked, a Māyāvādi will prefer to call himself an Advaita Vedāntin.

As we will study throughout this book, the Brahma-sūtras directly contradict the Māyāvāda philosophy, by stating that Brahman has transcendental qualities, is describable in words, that māyā is subordinate to Brahman, that the material world comes from the molding of the external potency and is thus not false, that the individual soul is simultaneously one and different from the Supreme Brahman, and so on. When the word jugglery is removed, the true meaning of the sūtras becomes apparent.

Śankarācārya is not to blame for the deviations introduced by his followers, since he came with a specific mission, doing what was necessary at the time. His followers, however, failed to understand the real purpose of his teachings, which was to prepare the path for Rāmānujācārya, Madhvācārya, Nimbārka, and Viṣṇusvāmī, gradually establishing the proper conclusions of the scriptures, opening in turn the gates for the advent of Sri Caitanya Mahāprabhu.

Later in life, Śankarācārya started speaking more about devotion to the Lord, hinting at his true mission of gradually elevating his followers. In his last words, Śankarācārya famously expressed his devotional sentiments:

bhaja govindam, bhaja govindam, bhaja govindam mudha-mate

samprapte sanhite kale, na hi rakshati duhkrin karane

“Worship Govinda, worship Govinda, worship Govinda, you fools and rascals! Your rules of grammar and word jugglery will not help you at the time of death.”

These words are part of a composition called Moha Mudgara (The Hammer of Delusion), which he composed in the later period of his life when he saw an old, learned paṇḍita absorbed in studying difficult Sanskrit grammar rules, still in the mood of vain intellectual pursuits and debate, blind to the proximity of death. Seeing him, Śankarācārya became compassionate and composed a song to convey a vital truth: devotion to the Lord is the only path to liberation, and mere intellectual pursuits without devotion are ultimately fruitless. This song brings many conclusions that are explained in the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, such as the idea that devotional service to the Lord can easily purify one of all sins, that other processes are ineffective unless mixed with bhakti, and that this is the true process to become free from birth and death.

Here are some other verses included in his song:

bhagavad-gītā kiñcid adhītā, gangā-jala-lava-kaṇikā pītā

sakṛd api yena murāri samarcā, kriyate tasya yamena na carcā

“If one has studied even a little of the Bhagavad Gītā, drunk a drop of Ganges water, and worshiped Lord Murari (Kṛṣṇa) at least once, he will not meet with Yamaraja at the time of death [he will be purified of all sins]”.

punarapi jananam punarapi maraṇam, punarapi jananī jaṭhare sayanam

iha samsāre bahudustāre, kṛpayā’pāre pāhi murāre

“Again and again being born, again and again dying, and again and again staying in the mother’s womb. Save me from this ocean of death, O Murari, through Your infinite compassion!”

yogarato vā bhogarato vā, sangarato vā sanga vihīnaḥ

yasya brahmaṇi ramate cittam, nandati nandati nandaty eva

“One may be immersed in yoga or in sensory pleasures, attached to worldly duties or detached from them; but he whose mind delights in Brahman (the Supreme Lord, Kṛṣṇa), he indeed rejoices, repeatedly rejoices, and only rejoices [he is saved from material suffering, attaining the Supreme].”

Next: The Vaishnava schools »

You can also donate using Buy Me a Coffee, PayPal, Wise, Revolut, or bank transfers. There is a separate page with all the links. This helps me enormously to have time to write instead of doing other things to make a living. Thanks!

« Vedānta-sūtra: The Govinda-bhāṣya of Baladeva Vidyābhūṣaṇa