Uncovering the soul’s eternal nature

Why and how did we come to this material world? How does our consciousness manifest here? Why is it so difficult to go back, and, even if we go back, how to be sure we will not return?

« The ‘Fall’ of the Jīva, as Explained by Śrīla Prabhupāda

Uncovering the soul’s eternal nature

What is our original nature? Why and how did we come to this material world? How exactly does our consciousness manifest here? Why is it so difficult to go back, and, even if we go back, how can we be sure we will not fall again? How exactly is Kṛṣṇa present here with us if He is transcendental, and how exactly are we ourselves present here, since we are also transcendental?

Questions like these may appear in the mind of a spiritual seeker at some point. To answer them is very difficult, because it deals with the intrinsic differences between our conditioned reality, existing under the purview of past, present, and future, and the eternal, permanent spiritual reality. However, when properly understood, the Sānkhya philosophy of Lord Kapila offers quite precise answers, which Śrīla Prabhupāda uses as a basis for his explanations. The reason we sometimes study the whole Śrīmad Bhāgavatam without finding answers to these questions is often that we don’t properly study these passages.

The main purpose of the Sānkhya system is to bring us back to our original transcendental position. For this, Lord Kapila explains the workings of the material world, the entanglement of the soul in the material energy, and the shortcomings of material life, together with the process of devotional service to the Lord that can free us from it. This combination of analytical knowledge and devotional service makes this process very effective, and we can understand why it is described in so much detail in the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam.

To explain the position of the soul in the material nature, Lord Kapila gives two examples: The sun reflected on water and a dream. When we see the reflection of the sun in a body of water, the reflection appears to be moving, following the movements of the water, while in reality the sun is fixed in the sky. A dream, on the other hand, is based on false identification. We accept the images we see in a dream as real, which often creates fear and suffering.

“The Personality of Godhead Kapila continued: When the living entity is thus unaffected by the modes of material nature, because he is unchanging and does not claim proprietorship, he remains apart from the reactions of the modes, although abiding in a material body, just as the sun remains aloof from its reflection on water.

When the soul is under the spell of material nature and false ego, identifying his body as the self, he becomes absorbed in material activities, and by the influence of false ego he thinks that he is the proprietor of everything. The conditioned soul therefore transmigrates into different species of life, higher and lower, because of his association with the modes of material nature. Unless he is relieved of material activities, he has to accept this position because of his faulty work.” (SB 3.27.1-3)

The example of the sun or the moon being reflected on water is given in many passages of the scriptures. In reality, the soul never mixes with matter. Because the soul is of a different nature, this mixture is not possible. Instead, the soul remains always aloof, just as oil on water. However, the consciousness of the soul is reflected in matter, just like the sun or moon may be reflected in a lake or any other body of water. The reflection may thus appear to be wavering, but this doesn’t mean the sun or moon is wavering.

Sometimes this example is used to explain the difference between the Lord and the jīvas. The Lord is like the sun in the sky, completely unaffected, while the conditioned soul is compared to the reflection, being affected by the movements of the water. In this case, however, Lord Kapila is using the same example to explain the difference between a conditioned soul and a liberated soul. The conditioned soul identifies with the reflection on water and thus suffers or enjoys according to the movement of the three modes. A liberated soul, however, identifies with his real identity, transcendental to matter. This example is certainly appropriate. “Tat tvam asi”: a liberated soul is as good as the Lord. Just as the Lord is transcendental, the liberated soul is also transcendental.

How can we be elevated to this level of understanding? As Prabhupāda mentions, vāsudeve bhagavati bhakti-yogaḥ prayojitaḥ (SB 1.2.7): when one engages fully in the activities of devotional service, bhakti-yoga, he becomes just like the sun reflected on water. Although a devotee appears to be in the material world, in reality, he is transcendental to it.

To be transcendental to the influence of the three modes does not mean one has to abandon everything and sit to chant under a tree. As Kṛṣṇa explains in the Bhagavad-gītā, a person working in Kṛṣṇa Consciousness is unaffected by karma, although performing all kinds of activities. Such activities in Kṛṣṇa Consciousness are called akarma, transcendental activities that liberate us from karma. It depends thus more on one’s consciousness since everything can be used in the service of the Lord.

As Prabhupāda explains in his purport:

“Avikāra means “without change.” It is confirmed in Bhagavad-gītā that each and every living entity is part and parcel of the Supreme Lord, and thus his eternal position is to cooperate or to dovetail his energy with the Supreme Lord. That is his unchanging position. As soon as he employs his energy and activities for sense gratification, this change of position is called vikāra. Similarly, even in this material body, when he practices devotional service under the direction of the spiritual master, he comes to the position which is without change because that is his natural duty. As stated in the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, liberation means reinstatement in one’s original position. The original position is one of rendering service to the Lord (bhakti-yogena, bhaktyā).”

On the other hand, when a soul comes under the strong influence of the false ego, he sees himself as the body and thinks that he is performing actions and is the proprietor of everything. In other words, he identifies with the reflection in the water, instead of his original position in the sky. By identifying with the gross and subtle bodies in this way, he has to enjoy or suffer according to the fate of the body. One has to experience death, suffer in hell, and so on. The soul does not die or go to hell, but by identifying with this particular material identity, the soul has to go through such experiences. Ultimately, all types of material activities are bad because they reinforce this identification with the body and create results that extend our existence in this material world. Pious activities are a little better because they may, over time, bring one to the platform of goodness, but they also lead one to another material body. The only solution is to perform akarma, activities performed in devotional service that don’t produce material results.

As Prabhupāda mentions, “One who desires material liberation has to turn his activities to devotional service. There is no alternative.”

What about the example of the dream?

“Actually a living entity is transcendental to material existence, but because of his mentality of lording it over material nature, his material existential condition does not cease, and just as in a dream, he is affected by all sorts of disadvantages. It is the duty of every conditioned soul to engage his polluted consciousness, which is now attached to material enjoyment, in very serious devotional service with detachment. Thus his mind and consciousness will be under full control.” (SB 3.27.4-5)

Here, Lord Kapila gives another example to illustrate the position of the soul in the material world. Our position here is similar to a dream, where we suffer and enjoy many illusory situations that have no connection with our real position.

One may dream that he is in a dark forest and feel fear, or even have a nightmare, dreaming he is dying, being devoured by a tiger. Both are simply due to his delirious condition. There is no possibility of one being killed by the illusory tiger he sees in a dream. The tiger inside the dream does not affect reality, and one can easily understand that as soon as he finally awakens from the dream.

In the Bhagavad-gītā, Kṛṣṇa explains that the soul is immortal and can’t be harmed by any type of weapon. This shows how all the threats we fear in this world are just like the tiger in the dream. The soul has his real existence outside of this material creation, and as soon as we wake up from it, we can clearly see that all the fear and lamentation we experienced here were nothing more than a dream.

A dream is not false; it exists on a subtle level, and we are experiencing it. The defect is that we accept the situations created in the dream as real, and thus we enjoy or suffer. A similar example is a movie. A movie is not false; it exists. The fault is when we identify with the characters in the movie and start thinking that it is real. In this case, we laugh and cry following their adventures, although in reality, it has nothing to do with our lives. In other words, both the dream and the movie are real, but they have nothing to do with our real existence. What happens inside the dream or the movie has no effect in the real world.

Similarly, this whole material creation is like the dream of Mahā-Viṣṇu. He creates it as an alternate reality for the souls who want to forget their real lives and temporarily join the dreamland. Being parts and parcels of the Lord, we join Him in His dream and thus are placed in this material world. The material world is thus not false; the problem is in accepting what we experience here as reality. Kṛṣṇa Consciousness means to focus on our real life of service to Kṛṣṇa, and gradually wake up from the dream.

As Prabhupāda explains, “The best service to the people in general is to awaken them to Kṛṣṇa Consciousness so that they may know that the supreme enjoyer, the supreme proprietor and the supreme friend is Kṛṣṇa. Then this illusory dream of lording it over material nature will vanish.”

Living in the dream means to think of ourselves as the enjoyers, the proprietors, the objects of attention, the maintainers of others, and so on. In the spiritual world, Kṛṣṇa is the center of attention of everyone. He maintains everyone, is the friend of everyone, and is the Supreme proprietor and enjoyer. Life in this material world means trying to imitate Kṛṣṇa. When we think like this, māyā covers our consciousness, and we become engaged in so many material activities, trying to enjoy this world and help others to also enjoy. A gross materialist uses his money to enjoy his senses to the best capacity, while a pious materialist performs charity and uses his money to help others to satisfy their senses. In both cases, the object of service is the material senses. The pious materialist is considered a little better, but both are an illusion and are in practice more or less the same.

The basic principle of bhakti-yoga is to accept that Kṛṣṇa is the proprietor, Kṛṣṇa is the enjoyer, Kṛṣṇa is the maintainer, the friend, etc., and that all our actions should be performed in cooperation with His desire. Being Kṛṣṇa conscious means accepting these principles and then trying to broadcast them and present this knowledge to others. The sound of the holy names and descriptions of Kṛṣṇa’s form, qualities, pastimes, etc., is non-different from Kṛṣṇa, and they can thus elevate our consciousness, connecting us with Him.

Achieving the transcendental platform

What is the process to elevate ourselves to this spiritual consciousness? How can we wake up from the dream? In many passages, Prabhupāda extends the analogy of the dream by explaining that when we are dreaming, all the senses are dormant, except hearing. When we hear someone shouting that there is fire, we immediately wake up, and thus we can be saved. Similarly, when we are sleeping under the spell of māyā, absorbed in the dream of material creation, the only way we can be awakened is by sound coming from the other side, from the spiritual world. This transcendental sound pierces through the coverings of the universe and awakens us to our real consciousness. Sound is the first material manifestation, appearing together with the element ether. Sound is thus the frontier between the material and the spiritual. It is the medium through which the transcendental reality can become manifest in our plane. This is also indicated by Lord Kapila:

“One has to become faithful by practicing the controlling process of the yoga system and must elevate himself to the platform of unalloyed devotional service by chanting and hearing about Me.

In executing devotional service, one has to see every living entity equally, without enmity towards anyone yet without intimate connections with anyone. One has to observe celibacy, be grave and execute his eternal activities, offering the results to the Supreme Personality of Godhead.” (SB 3.27.6-7)

Here, he mentions the system of āṣṭānga-yoga, composed of eight stages, starting from yama and niyama (rules and regulations, what to do and what not to do), but the emphasis is on the goal, the idea of attaining the platform of unalloyed devotional service. Lord Kapila initially described the Sānkhya system in Satya-yuga, when people used to practice meditation, but the emphasis is on the practice of devotional service. There are different processes offered in the Vedas, such as karma, jñana, mystic yoga, etc., but all these processes are more or less useless without being combined with bhakti. When bhakti is added, these processes become, respectively, karma-yoga, jñana-yoga, āṣṭānga-yoga, etc., and become effective. These processes are thus secondary; the main component is bhakti, which has its foundation in the process of hearing and chanting.

As Prabhupāda explains, “Yoga is practiced in eight different stages: yama, niyama, āsana, prāṇāyāma, pratyāhāra, dhāraṇā, dhyāna and samādhi. Yama and niyama mean practicing the controlling process by following strict regulations, and āsana refers to the sitting postures. These help raise one to the standard of faithfulness in devotional service. The practice of yoga by physical exercise is not the ultimate goal; the real end is to concentrate and to control the mind and train oneself to be situated in faithful devotional service.”

Often, we have the impression that hearing and chanting is the process for Kali-yuga, and people in other eras were following other processes, but this is not actually true. In Satya-yuga, hearing and chanting were performed by pronouncing the sacred syllable Om, which is another form of the Mahā-mantra. During Treta-yuga, hearing and chanting were done by the recitation of mantras during fire sacrifices, and in Dvāpara-yuga by reciting mantras during deity worship. The process is thus the same for all ages, just the external format changes. Without being engaged in the process of hearing and chanting, there is no possibility of attaining perfection.

Even after being situated in Kṛṣṇa Consciousness, we still have to continue living in this body until it expires. This is valid not only for us but also for demigods and others, who have to finish their long lives before they can go back to Godhead. The next question is thus how we should act in this world after being situated on the platform of devotional service? The two verses quoted contain the answer.

a) A devotee should see all living beings as equal, seeing the soul and not the body. Understanding that every soul is dear to Kṛṣṇa and that He is personally residing in every body as Paramātmā, we should not have enmity towards any living being, even the ones who act in unpleasant ways, understanding that they all act according to their respective natures, according to the three modes.

b) Not feeling enmity is, however, just part of it. We should also not have attachment. In previous ages, people used to live in the forests, where they could practice devotional service without having contact with anyone. An easier process, however, is to just associate with other devotees engaged in devotional service. The essence is not to just be alone but to avoid intimate association with materialistic people. Association with devotees who inspire us in our devotional service is always welcome.

What about relationships with family members, friends, etc? Ideally, one should explain Kṛṣṇa Consciousness to them. If we can make our family members devotees, or if at least they become receptive to hearing about Kṛṣṇa from us, our association with them can be very inspiring in our spiritual path. If they are not interested, we may externally associate with them following normal social norms, without attachment or aversion. We may then just agree with whatever they say, without being very intimate with them.

c) Lord Kapila mentions two other qualities, maunena and sva-dharmeṇa. Maunena means practicing gravity, avoiding speaking more than necessary. Gravity and introspection are two other factors that are very favorable for a saintly life. Speaking more than necessary about mundane topics just serves to agitate the mind. However, just as performing activities in devotional service is considered inaction, or akarma, speaking about Kṛṣṇa is considered mauna, or silence.

The final quality is sva-dharmeṇa, being occupied in one’s dharma. There are two levels of performance of dharma. The first is the naimittika-dharma, or ordinary duties based on one’s position in society, family connections, and so on. In the Bhagavad-gītā, Kṛṣṇa advises us to practice such duties with a spirit of detachment, as an offering to Him until we ascend to a liberated platform, and after that as a way to give a good example to others. The second level is nitya-dharma, or the cultivation of our eternal attitude of devotional service to Kṛṣṇa. This should be our primary occupation.

This description continues in the next verses:

“For his income a devotee should be satisfied with what he earns without great difficulty. He should not eat more than what is necessary. He should live in a secluded place and always be thoughtful, peaceful, friendly, compassionate and self-realized.

One’s seeing power should be increased through knowledge of spirit and matter, and one should not unnecessarily identify himself with the body and thus become attracted by bodily relationships.

One should be situated in the transcendental position, beyond the stages of material consciousness, and should be aloof from all other conceptions of life. Thus realizing freedom from false ego, one should see his own self just as he sees the sun in the sky.” (SB 3.27.8-10)

The soul doesn’t depend on food, shelter, or anything else in this material world, but the body does. Since one should not destroy his material body, understanding that the body is the property of Kṛṣṇa and should thus be used in His service, one has to maintain it until it expires by itself. This demands being involved in material activities to a certain extent. How can we do that while at the same time keeping ourselves on a pure platform?

Materialistic people usually work very hard to improve their material condition. One who is poor works to escape poverty, and one who is well-to-do works equally hard to increase his income. This comes from the desire to lord over material nature. The more money one has, the more possibilities one has in the material sphere; therefore, most people are very attracted to material wealth. Lord Kapila, however, doesn’t recommend that we enter into the rat race.

Instead, he emphasizes the word yadṛcchayā, which means “by its own accord”. As Prabhupāda explains, “every living entity has a predestined happiness and distress in his present body; this is called the law of karma. It is not possible that simply by endeavoring to accumulate more money a person will be able to do so, otherwise almost everyone would be on the same level of wealth. In reality everyone is earning and acquiring according to his predestined karma. According to the Bhāgavatam conclusion, we are sometimes faced with dangerous or miserable conditions without endeavoring for them, and similarly we may have prosperous conditions without endeavouring for them. We are advised to let these things come as predestined.”

Contradictory as it may seem, working hard does not make one more wealthy. On the contrary, Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam lists working too hard as one of the factors that bring misery. We can see this in practice. Most people work hard in modern societies all over the world, but just a small part of them become wealthy. If working hard would make one rich, everyone who works hard would earn the same, but that’s not what we see. The point is that one earns according to his previous karma. The scriptures thus recommend that we work according to our prescribed duties and be satisfied with the income that comes naturally as a result of such work. This will probably consume one-third of our time or so. The rest should be used to perform our other duties, connected with our families, and so on, and especially invested in our practice of Kṛṣṇa Consciousness. By being balanced in our activities, we will attain the best results.

If our karma is to become rich, money will come naturally by just performing our duties, and if being rich is not in our future, working more than required will not improve the situation. Quite the opposite: working more will make us neglect other duties, and especially neglect our practice of Kṛṣṇa Consciousness, which will make us miserable in the end. Therefore, Lord Kapila says that “a devotee should be satisfied with what he earns without great difficulty.”

The next recommendation is mita-bhuk; we should eat little, just as necessary to keep the body healthy. Overeating increases the influence of the mode of ignorance, which in turn covers our consciousness and brings material misery. We can practically see that overeating is behind most health problems. Eating little, on the other hand, helps us to ascend to the mode of goodness, which brings self-control, health, peace, and self-satisfaction. If we can learn to control our tongue and eat just what is necessary, we will have more facilities to conduct our spiritual practice. Apart from quantity, the quality of what we eat is also important. This is taken care of when we eat only pure and wholesome food offered to Kṛṣṇa.

Lord Kapila also recommends vivikta-śaraṇaḥ, living in a secluded place. Nowadays, most people live in big cities because they offer more material conveniences, but these are not very good places for spiritual practice. Instead, a devotee should seek to live close to other devotees who are serious about practicing devotional service. Living in a community brings some inconveniences, but wasting our human form of life and having to accept another material body, possibly in difficult conditions, is a much worse outcome.

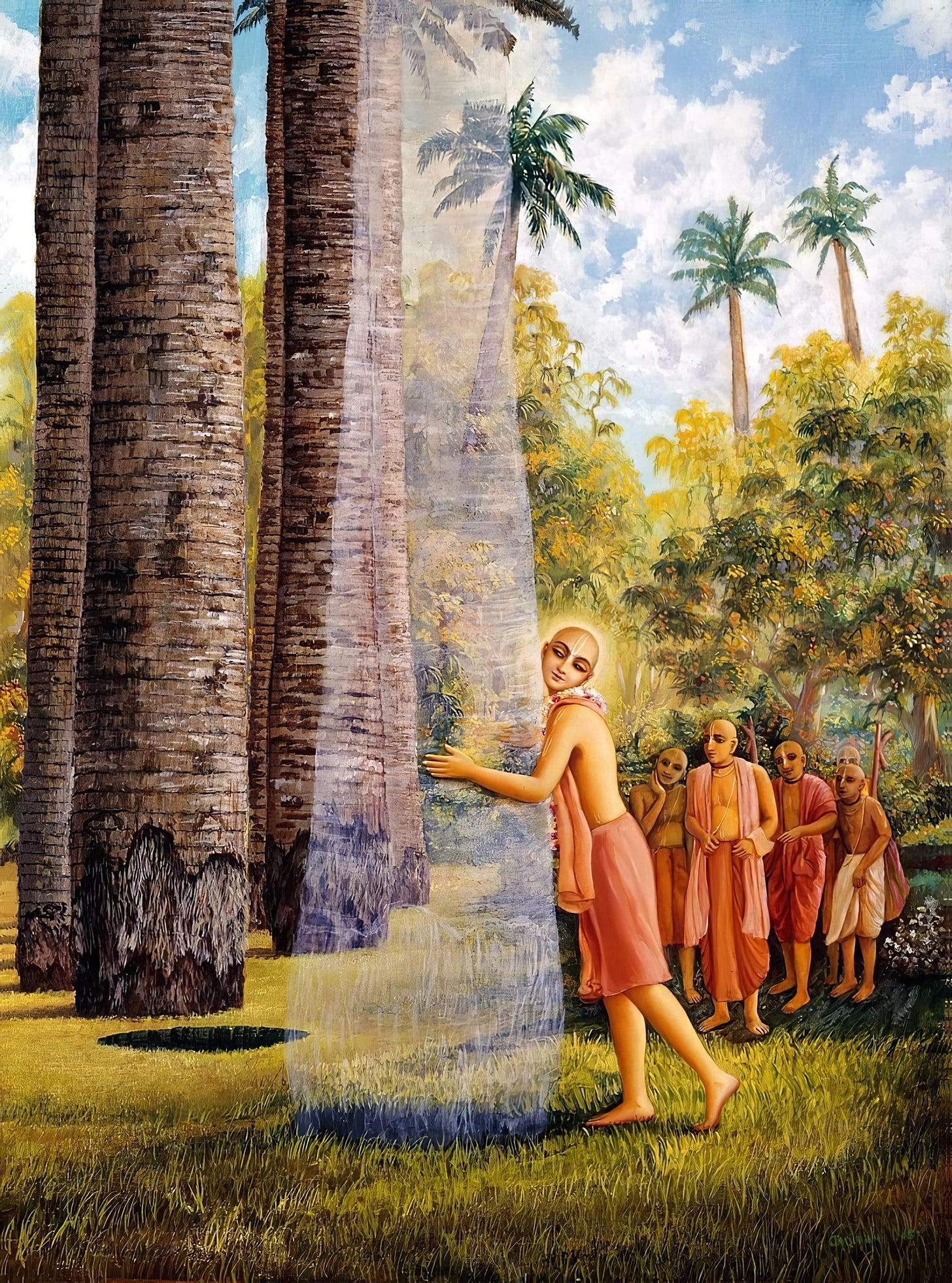

By this practice, combined with the cultivation of spiritual knowledge, we can develop spiritual vision, seeing ourselves as separated from matter. In this way, we can gradually reduce our identification with the body and relationships based on the body, and gradually come to the transcendental position, realizing our eternal nature as souls. As Lord Kapila mentions, “one should see his own self just as he sees the sun in the sky.” We should identify with our true nature, and not with the reflection.

The word mentioned is “ātmānam”, which means “the Self”. In the word-for-word, as well as in the translation, Prabhupāda goes with the direct meaning of the word, translating it as “his own self”. However, in the purport, Prabhupāda opens up the deeper meaning of the term, meaning our identification with our eternal identity as a servant of the Supreme Lord, who is present everywhere. Seeing ourselves thus, in the higher sense, means becoming free from the false egoistic identification with the body, and instead seeing ourselves as eternal servitors of the Lord. When we can establish ourselves on this platform, we can always see Kṛṣṇa, both outside and inside.

The Chāndogya Upaniṣad describes a spiritual nature, “para”, which is present everywhere. Impersonalists interpret this as the impersonal Brahman, but as Vaiṣnavas, we understand that this all-pervading nature is Kṛṣṇa, present everywhere as Paramātmā. We are parts and parcels of Kṛṣṇa, and thus we are all also part of this spiritual, blissful, all-pervading nature. As Lord Kapila mentions, when we attain self-realization, we can see Kṛṣṇa everywhere, just as we can see the sun.

You can also donate using Buy Me a Coffee, PayPal, Wise, Revolut, or bank transfers. There is a separate page with all the links. This helps me enormously to have time to write instead of doing other things to make a living. Thanks!