Beyond temporary happiness and distress (Bg 2.14 and 2.15)

Just as the bodies we accept in this world are temporary, all the pleasant and unpleasant situations we face are also impermanent. No one experiences only happiness, and no one faces only distress.

« The Song of God: An in-depth study of the Bhagavad-gītā (Volume 1)

Verse 14: mātrā-sparśās tu kaunteya, śītoṣṇa-sukha-duḥkha-dāḥ

āgamāpāyino ’nityās, tāms titikṣasva bhārata

O son of Kuntī, the nonpermanent appearance of happiness and distress, and their disappearance in due course, are like the appearance and disappearance of winter and summer seasons. They arise from sense perception, O scion of Bharata, and one must learn to tolerate them without being disturbed.

Verse 15: yam hi na vyathayanty ete, puruṣam puruṣarṣabha

sama-duḥkha-sukham dhīram, so ’mṛtatvāya kalpate

O best among men [Arjuna], the person who is not disturbed by happiness and distress and is steady in both is certainly eligible for liberation.

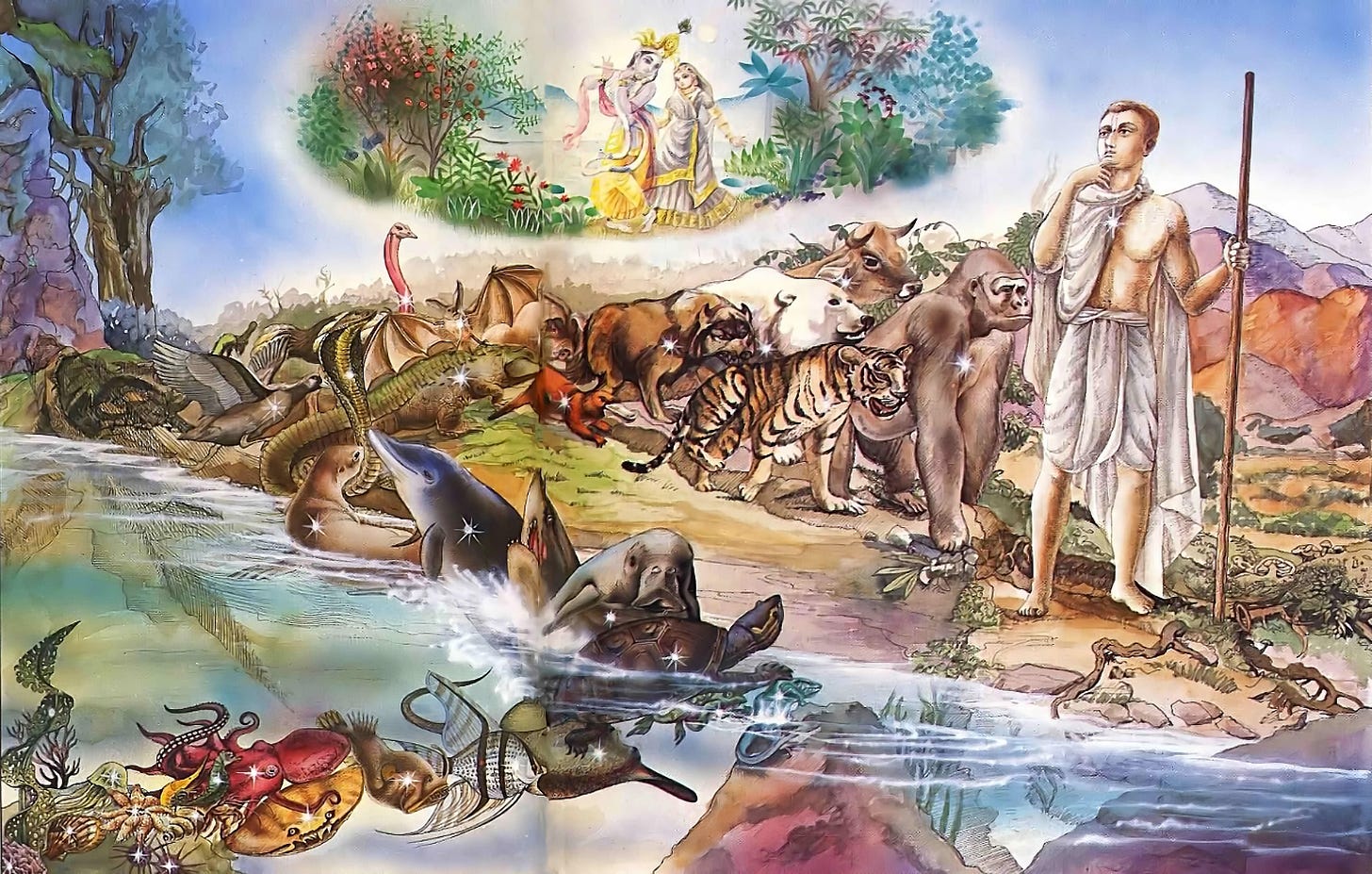

Just as the material bodies we accept in this world are temporary, all the pleasant and unpleasant situations we face are also impermanent. No one experiences only happiness, and no one faces only distress. Our lives are always a combination of both, according to the results of our previous actions. Just as distress comes automatically, without us having to look for it, whatever happiness we are entitled to also comes automatically. The two come in perpetual succession, just like the seasons of the year. Just like we can't stop winter from coming after fall, and summer from coming after spring, we can't stop happiness and distress from coming in their due time. Just like a person in knowledge is not confused by the change of body, we should not be disturbed by this temporary transition. Instead, we should keep focus on what is permanent.

An important word in this verse is the word "anityāḥ" in the third line. Because of Sanskrit rules, it is written as "’nityās", because the "a" is suppressed by the "o" in the previous word, but you can see it appears in the full form in the word-by-word meaning given by Prabhupada. Anityāḥ means nonpermanent, the opposite of the word nityā from the nityo nityānām verse we just studied. Both sukha and duḥkha (happiness and distress) we experience are āgama apāyinaḥ, they come and go, appear and disappear. Therefore, tān titikṣasva: we should try to tolerate them without being disturbed.

With words like nitya and anityāḥ, sat and āsat, etc. Krsna is drawing a picture, helping us to understand the difference between the permanent and the impermanent, the eternal and the illusory. This mental picture is essential to properly understand all the intricate concepts He explains in the rest of the Gītā.

In his purport, Prabhupada emphasizes the performance of duties despite such transitory circumstances. Duties connected with dharma bring us eternal results by gradually awakening us to our original, eternal nature as souls. The benefit of achieving self-realization is unlimited because it results in permanent happiness, while the discomfort we face in following spiritual principles is transitory. The performance of such duties should thus receive priority over trying to obtain or sustain temporary happiness. A bar of gold has more value than any amount of fake money, and similarly, any amount of spiritual progress is more valuable than any amount of transitory material happiness.

Even if we don't look for it, material happiness will still come, therefore, we don't lose anything by practicing self-realization, even in material terms. All we need to sacrifice is the illusory hope of achieving a permanent position of happiness in this world, which is impossible in any case.

When it is winter, our instinct is to avoid cold water, but in times before the invention of electrical and gas showers, brāhmaṇas would wake up early and take a bath in cold water to perform their morning religious duties. The cold would pass, but the merits they would incur for performing their duties despite the discomfort would be permanent. Similarly, we avoid being close to fire when it is hot, but a housewife would not hesitate to cook for her family, even in the hottest part of the summer. Krsna implies that Arjuna should similarly perform his duties as a kṣatriya despite all inconveniences because this is what is going to benefit him in the long run. Without executing one's duties, it is difficult to be elevated to a platform of knowledge, because true spiritual realization comes from executing duties without attachment, as Krsna will explain in the next chapters of the Bhagavad-gītā.

An extra dimension to this topic is given by the words "mātrā-sparśāḥ" in the first line of the 14th verse. Mātrā-sparśāḥ means perception of the senses. The same cold water that we avoid in the winter becomes a source of pleasure in the summer. Even during the winter, people feel pleasure in taking a cold bath after taking a sauna, for example, and others may come to like it out of habit. Similarly, animals like seals feel pleasure in playing in cold water even in the winter because they have bodies adapted to it. The cold water is the same, but the perception of it as pleasant or unpleasant comes from one's mental and sensorial perception. Ultimately, we live in a dark room inside of the body, and everything we experience in this world is just the result of electrical signals coming to our brains and being interpreted by our minds and intelligence. Our perception of reality, being pleasant or unpleasant, is ultimately the result of this interpretation, and thus, our perception of reality has often very little to do with what reality is.

Just as a person in a serious state of depression will feel everything as being unpleasant, a person with a more positive attitude will see the positive side and see the same situations as pleasant or neutral. Our mental status has thus a more direct influence on our perception of happiness or distress than the physical situation we are in, and the way to change our mental situation is by spiritual realization. That's what the Bhagavad-gītā brings to our lives.

Ultimately, we should become dhīras, wise persons who due to spiritual realization understand the transitory nature of this world and become thus sama-duḥkha-sukham, equipoised (sama) in both material distress (duḥkha) and material happiness (sukham), understanding their transitory nature.

Holding a piece of ice or having our head put inside of water doesn't sound so bad if we know it will last for just 30 seconds. Similarly, any distressing position in this world is not so bad when we understand it lasts for just a little while. The soul is eternal, and compared to eternity, a few days, months, or even years are insignificant. A wise person who understands that learns to tolerate temporary unpleasant situations to obtain eternal happiness.

Everything starts with jñāna or theoretical knowledge. That's what we receive by reading a book or hearing a lecture, for example. As we practice this knowledge, however, it is gradually converted into vijñāna, or realized knowledge, and that's precisely the knowledge that can change our mental situation and bring us to self-realization. In this portion of the Bhagavad-gītā, from verse 2.12 to verse 2.38, Krsna explains transcendental knowledge according to cause and effect using logic. This process of analysis is called Sānkhya and is also used by Lord Kapila in his teachings in the third chapter of the Srimad Bhagavatam. Although the contents are different, the teachings of Krsna in the Gītā and the teachings of Lord Kapila in the Srimad Bhagavatam are in another sense the same, because they lead us to the same conclusions about the soul and the goal of life.

Main points in the purports of Srila Prabhupada:

"O son of Kuntī, the nonpermanent appearance of happiness and distress, and their disappearance in due course, are like the appearance and disappearance of winter and summer seasons. They arise from sense perception, O scion of Bharata, and one must learn to tolerate them without being disturbed."

a) The performance of duties is given great importance in the Vedas because one has to follow these principles in order to rise up to the platform of knowledge. In the proper discharge of duty, one has to learn to tolerate temporary happiness and distress, like a brāhmaṇa taking a cold bath and a housewife cooking in the summer to feed her family.

b) Realized knowledge combined with devotion can liberate us from the clutches of māyā (as described in the 2nd chapter).

c) Arjuna is addressed as Kaunteya because of his greatness from the mother's side, and Bhārata from the father's side. From both sides he is supposed to have a great heritage and thus Krsna inspires him to perform his duty without hesitation.

"O best among men [Arjuna], the person who is not disturbed by happiness and distress and is steady in both is certainly eligible for liberation."

a) A person becomes eligible for liberation by remaining steady in his determination and tolerating distress and happiness in the advanced stage of spiritual realization. One example is the sannyāsī, who perseveres in all kinds of difficult situations. It is difficult, but if anyone is able to tolerate such difficulties, his path to spiritual realization is complete.

b) Similarly, Arjuna is advised to persevere in his duties as a kṣatriya, despite the difficulties in fighting against his family members and friends. Achieving liberation from material bondage passes through performing duties for a higher cause, despite the difficulties.

« The Song of God: An in-depth study of the Bhagavad-gītā (Volume 1)